Canine Dystocia

Amanda A. Cavanagh, DVM, DACVECC, Colorado State University

Part 2: Neonatal Resuscitation

Dystocia is a difficult or prolonged parturition that is a reproductive emergency requiring medical or surgical intervention by a skilled team to minimize perinatal mortality. Dystocia can occur because of problems with the bitch or the fetus, and treatment depends on the cause. Clear communication between veterinary team members and the client throughout the patient's pregnancy and during her emergency care will help set accurate outcome expectations.

Dystocia can be a high-stakes emergency for clients and veterinarians because beloved pets, potentially valuable genetic attributes, and financial investments are at risk.

Whelping occurs 62 to 64 days postovulation. If ovulation timing is unknown, whelping is estimated to occur 56 to 72 days postbreeding because of the variation in proestrus and estrus between individual animals.1-3 There are 3 stages of labor.

Stage I is clinically manifested as restlessness, nesting, and a 1ºF decrease in body temperature, often to <99ºF. During this 6- to 12-hour period, progressive uterine contractions and cervical dilation occur.3-5

Stage II is characterized by fetal expulsion of an average of one puppy per hour.3,5 Fetal death rate increases with prolonged stage II labor, and rapid intervention is essential to minimize fetal loss.3

Stage III is characterized by the passage of the placenta and fetal membranes.3 Typically, stages II and III alternate until all fetuses are delivered.3,5

Dystocia is the most common emergency during birth, with an occurrence rate of 2% to 5% in dogs.6 Risk factors include maternal body size, breed, and litter size (eg, single fetus vs large litter). Older primiparous bitches (ie, those whelping a litter for the first time) are at greater risk.7 Maternal factors cause dystocia in 75% of cases, and fetal factors are involved in 25% of cases.8,9 (See Causes of Dystocia in Dogs.) Certain breeds have a higher incidence of dystocia and a greater need for medical intervention or cesarean delivery.

Causes of Dystocia in Dogs3

Maternal Factors

Primary and secondary uterine inertia*

Uterine torsion

Vaginal abnormalities (eg, strictures)

Pelvic abnormalities (eg, small size, fracture, neoplasia)

Systemic illness, infection

Malnutrition

Genetics (terrier breeds)

Fear, stress

Fetal Factors

Malpresentation*

Fetal malformation

Fetal monster

Anasarcous fetuses

Cephalopelvic disproportion

Fetal oversize

Litter size (eg, inadequate stimulation from too few fetuses, overstretching from too many)

Fetal death

* Most common causes of canine dystocia in the maternal and fetal categories

Breeds at Increased Dystocia Risk3

Boston terrier

Bulldog

Clumber spaniel

French bulldog

German wirehair pointer

Mastiff

Pekingese

Scottish terrier

Dystocia Diagnosis & Treatment Plan

Diagnosis of dystocia is based on gestation length and labor history, physical examination findings, and imaging studies results.The cause must be determined so the appropriate treatment modality can be chosen.8 A full physical examination, including a digital vaginal examination, is a priority.8

Dystocia Diagnostic Criteria3

Historical Information

>72 days postbreeding or prolonged gestation when ovulation date is known

Failure to deliver within 24 hours of beginning stage I labor or body temperature decreasing to <99ºF

Green or black vaginal discharge before delivery of first puppy

Straining for >1 hour continuously without a delivery

>3-hour lapse without active contraction between fetuses

Delivery of stillborn fetuses

Physical Examination Findings

Ill or distressed bitch

Vaginal hemorrhage during labor

Protrusion of fetal membranes for >15 minutes without delivery

Imaging Studies Results

Fetal heart rate <180 bpm

Radiographic evidence of dead or decomposing fetuses

Radiographic evidence of malpositioned fetuses, malformed fetuses, or a large fetus exceeding the maternal pelvic canal diameter

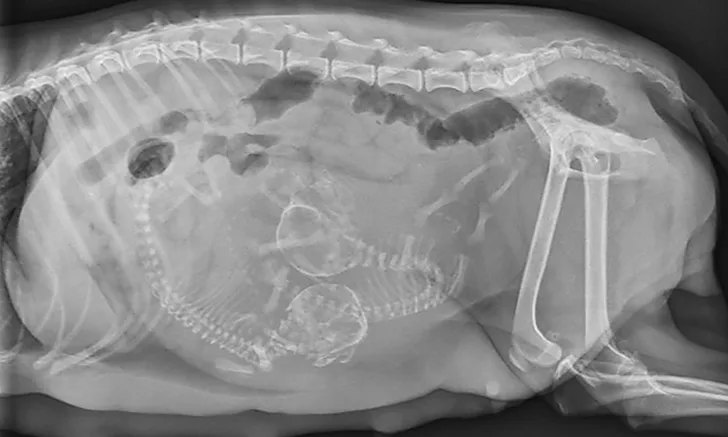

FIGURE 1

Ventrodorsal abdominal radiograph of a pregnant bitch presenting for dystocia. Note the malpositioned fetus oriented transversely to the pelvic canal. Radiographs courtesy of Amanda A. Cavanagh, DVM, DACVECC

If the bitch is examined after day 44 of gestation, when fetal skeletons mineralize, radiographs should be obtained to determine litter size, fetal positioning, and signs of fetal death.2,8 (See Figure 1 & Figure 2.) Ultrasonography is the ideal imaging modality for determining fetal stress and viability.2

Normal fetal heart rate is >220 bpm.

Heart rate <180 bpm or excessive fetal motion indicates fetal stress and hypoxia.10

Fetal heart rate <160 bpm indicates the need for immediate surgical intervention to prevent fetal loss.3,10

Medical management involves using ecbolic drugs (ie, agents that induce uterine contraction) and, less commonly, digital manipulation and removal of a fetus lodged in the birth canal. Malpresentation or malposition of the fetus can be corrected via careful and well-lubricated digital manipulation, as long as the fetus is of normal size.3 (See Figure 3.)

After careful, lubricated digital manipulation, a live fetus is delivered vaginally, still encased within the fetal membranes. Photo courtesy of Cory Woliver, DVM, Colorado State University College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences

Medical management of dystocia is pursued only when the bitch is healthy, the cervix is dilated, fetal size and positioning are appropriate for vaginal delivery, and fetal heart rate is normal.8 Common ecbolic drugs include oxytocin (0.25 units per dog IM or SQ q1h, to a maximum of 4 units per dog) and 10% calcium gluconate (0.5 mL/kg IV diluted 1:4 in sterile saline delivered over 20 minutes with continuous ECG monitoring). Oxytocin and calcium gluconate are typically administered concurrently.8,11-13 Hypoglycemia, although an uncommon cause of difficulty during whelping, should be aggressively treated with 50% dextrose (0.5-1.0 mL/kg IV diluted 1:4 in sterile saline).13 Ecbolic drugs are contraindicated in cases of obstructive dystocia.8

More than 60% of dystocia cases require surgical intervention, and cesarean delivery should be performed immediately if the fetal heart rate remains <150 bpm during a 3-minute ultrasonographic evaluation.3 Uterine rupture or torsion are absolute indications for cesarean delivery, and surgical intervention should be strongly considered for patients with obstructive dystocia, fetal stress indicated by heart rates 160 to 180 bpm, and primary or secondary uterine inertia.3

While planned cesarean deliveries carry a low risk and a favorable outcome, the risk to bitch or offspring increases when the procedure is performed as an emergency.3 Anesthetic protocols should minimize the time from induction to delivery, provide adequate maternal cardiovascular stability and analgesia, and minimize fetal depression. Fetal mortality increases with hypoxia and cardiopulmonary depression. Fetal blood pressure and perfusion are heart-rate dependent, so anticholinergic drugs should be part of the maternal premedication protocol to prevent fetal bradycardia3 and decrease vagal tone induced by intraoperative uterine traction.

Local analgesia, provided by opioid epidurals or local anesthetic nerve blocks, can minimize the need for general anesthetic drugs and augment postoperative maternal analgesia. Because inhalant anesthetics cross the placenta, their use should be minimized before the delivery of the fetuses.3 Opioids also cross the placenta and can lead to fetal depression, although buprenorphine has minimal transplacental transfer. All other opioids have a prolonged elimination time in the neonate and may require 2 to 6 days to metabolize.14 Short-acting opioids are an excellent choice in multimodal anesthesia protocols. Opioids can be reversed in affected neonates and provide analgesia to the bitch, which can minimize the need for inhalant or other injectable anesthetic drugs. Naloxone (administered as 1 drop sublingually, with possible repeated doses at 30-minute intervals) can help reverse opioid-induced depression in neonates.14 In the surgical suite, a group of skilled veterinary nurses or veterinarians should be available to resuscitate neonates upon delivery. Ideally, one resuscitator and all the necessary equipment that may be required should be available for each expected neonate.

Client Communication

Breeders should be aware of the financial investment required to produce healthy puppies. The veterinarian should educate each client about the risks for dystocia associated with a dogs breed, size, age, and prior need for cesarean delivery. Additionally, pregnant bitches should receive routine veterinary care, including abdominal radiography at 42 to 52 days postbreeding. Abdominal radiographs help evaluate the number of fetuses and may help predict the need for surgical intervention.

The client should be provided clear, written instructions that describe the clinical signs that warrant contacting the veterinarian. Print out and use our client handout, Caring for Your Pregnant Dog. The conversation should also include the suggestion that the pet should be spayed to prevent future pregnancies.

Conclusion

If a patients dystocia risk is significant, an emergency intervention plan should be put in place for either medical management, if appropriate, or elective cesarean delivery.

Take Action

Develop a practice protocol for fielding client inquiries about reproductive emergencies. Team members should be able to identify what constitutes an emergency when clients call with questions about a pregnant pet.

Provide clients of confirmed pregnant patients with clear, written instructions on the signs that indicate veterinary intervention is necessary.

If the patient is known to be a dystocia risk, have an emergency intervention plan in place.

This article originally appeared in the May 2017 issue of Veterinary Team Brief.