Clinician's Forum: Expert Views from a Roundtable on Osteoarthritis & Pain Management

Brought to you by Elanco

Participants

Mark Epstein, DVM, DABVP (Canine/Feline), CVPP, Senior Partner, Medical Director TotalBond Veterinary Hospitals

James Gaynor, DVM, MS, DACVAA, DAIPM, CVPP, President & Medical Director Peak Performance Veterinary Group

Duncan Lascelles, BSc, BVSc, PhD, FRCVS, DECVS, DACVS, Professor of Translational Pain Research & Management North Carolina State University

Carolina Medina, DVM, DACVSMR, CVA, CVPP, Veterinary Sports Medicine & Rehabilitation Specialist Coral Springs Animal Hospital

Sheilah Robertson, BVMS, PhD, DACVAA, DECVAA, DACAW, DECAWBM (WSEL), CVA, MRCVS, Senior Medical Director Lap of Love

Moderator

Mara Tugel, DVM, Elanco

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Radiographic signs of OA can be recognized in ≈40% of dogs by age 4, yet most cases are not diagnosed and treated until later in life. Thus, veterinary teams should try to educate owners about canine OA early in the patient’s life.

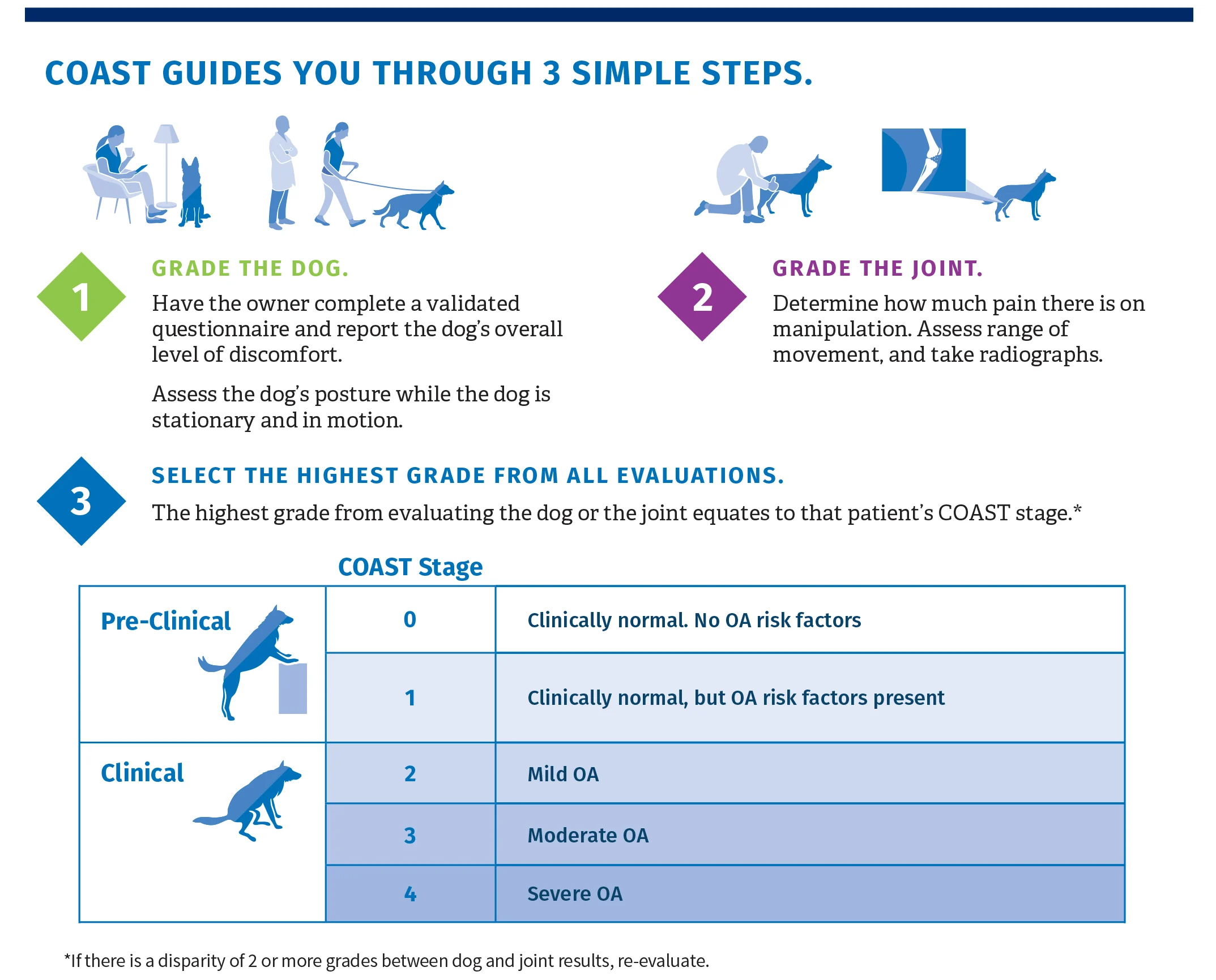

COAST is an OA staging tool that can be used to proactively screen all canine patients during routine examinations, facilitating earlier intervention in this progressive disease.

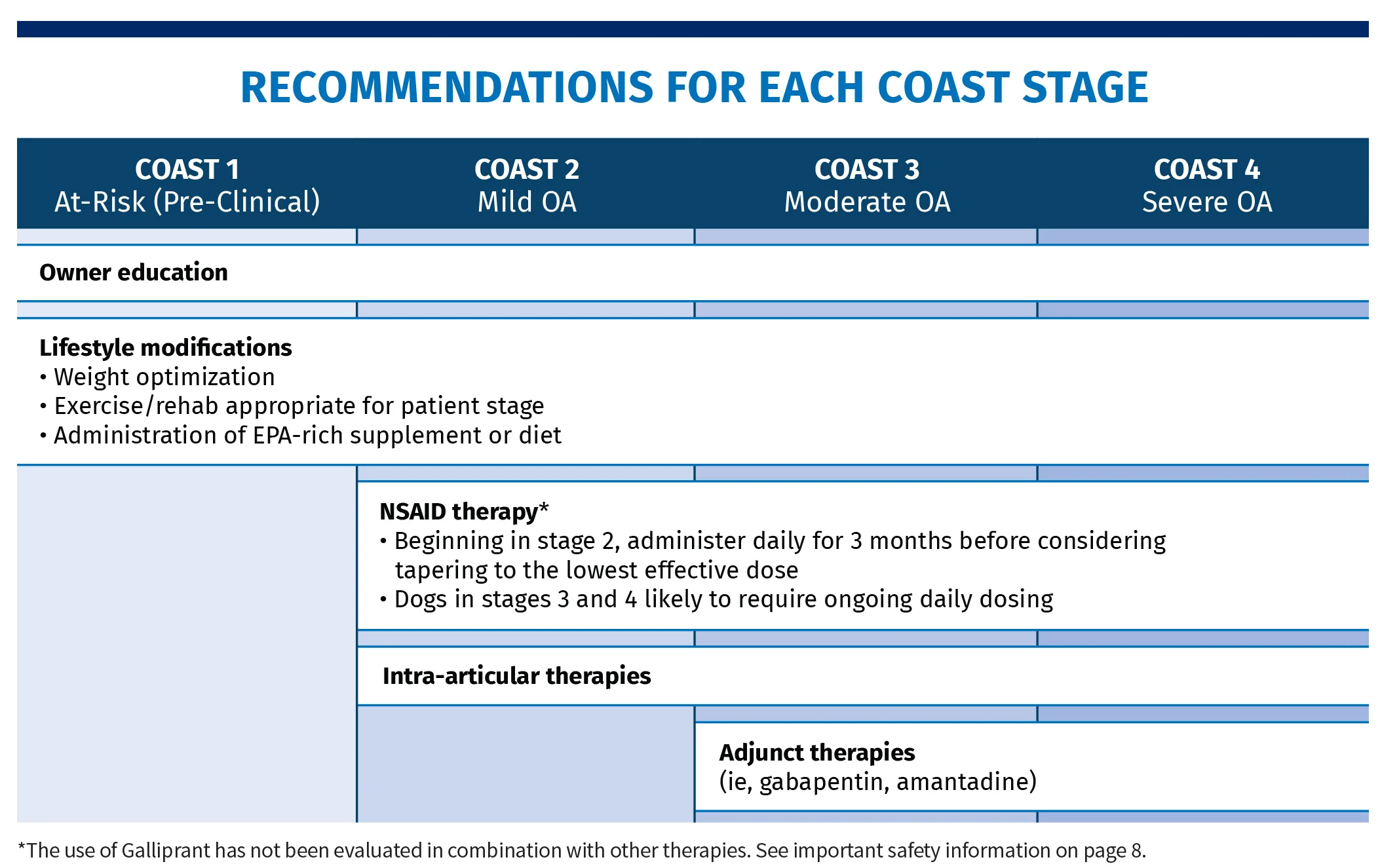

Lifestyle modifications such as weight loss, EPA supplementation, and exercise should be initiated for at-risk, pre-clinical COAST stage 1 patients and remain important throughout all stages of OA.

NSAIDs are indicated as soon as clinical signs of OA are present. Expert recommendation is to administer medication daily for 3 months before re-evaluating and considering tapering to the lowest effective dose. Dogs in COAST stages 3 and 4 are likely to require ongoing daily dosing due to disease severity.

Galliprant’s unique, targeted mode of action makes it different from COX-inhibiting NSAIDs and an ideal choice for earlier intervention and long-term treatment of OA.

In addition to NSAIDs, dogs in COAST stages 3 and 4 (moderate to severe OA) usually require adjunct medications and nondrug therapies to adequately control pain.

Intra-articular therapies can be considered in any clinical COAST stage for appropriate cases.

Although certain therapies are indicated for each COAST stage (see Recommendations for Each Coast Stage), treatment plans should be customized based on individual patient needs, which can vary greatly depending upon the joint(s) affected, clinical signs, and individual response to treatment.

A Paradigm Shift for Canine Osteoarthritis: Proactive Screening & Earlier Intervention

Approximately 40% of dogs have radiographic evidence of osteoarthritis (OA) by 4 years of age; however, most cases go untreated until much later in life. The Canine OsteoArthritis Staging Tool (COAST) can be used to proactively screen dogs for OA beginning at a young age and facilitates successful intervention earlier in the disease course. Once OA is diagnosed, dogs require treatment with proven effective analgesics such as NSAIDs, as joint supplements alone cannot address pain and inflammation associated with the disease. Galliprant (grapiprant tablets) is an NSAID with a unique mode of action that targets canine OA pain and inflammation while reducing the impact on GI, kidney, and liver homeostasis, making it an ideal choice for early intervention as soon as OA is recognized.

Dr. Tugel: What are the biggest challenges veterinarians face in helping dogs with OA?

Dr. Gaynor: I interact with a lot of primary care veterinarians, and for me, it tends to come down to the same issue: educating veterinarians that OA is a young dog issue. Primary care veterinarians have to educate owners A Paradigm Shift for Canine Osteoarthritis: Proactive Screening & Earlier Intervention Brought to you by Elanco early—at that first puppy vaccination at 8 weeks of age or whatever it may be. Start talking to them based on that pet’s breed, about risk factors, what to look for that we have predominantly overlooked before. These intermittent signs of OA that go away quickly are not necessarily innocuous events.

Dr. Medina: Early recognition can be challenging for the veterinarian and the client. I don’t get as many referrals for younger dogs, but the ones that I do see were typically out doing some kind of activity, then became lame and painful. Their vets told them to rest, and then they were told it was probably a strain or sprain or some type of soft tissue injury. Sometimes, I’ll get puppies that are referred and they’ve had several of these events in a few months’ time and I find they do have developmental orthopedic disease. So, I think it’s important to educate veterinarians that some of these signs clients are reporting might not necessarily be directly related to OA now but may be related to a risk factor that will develop into OA later on.

Dr. Lascelles: I think you’ve hit on something really important there. Education is an uphill struggle for a lot of reasons. There’s a lack of understanding that OA is driven by developmental disease. No one wants to hear it. Veterinarians don’t want to; owners don’t want to. And on top of all of that, owners may think, “Well, my dog’s still moving around, still goes upstairs. He might struggle, but he eventually gets in the car.” I think a lot of people say, “What’s the big deal?” I think it’s incumbent upon us to explain what the big deal is. It’s a huge deal when a dog can’t walk. When a big dog can’t get up, that’s an emergency. By acting early, we can prevent the “huge deal” problem; by intervening early, we can improve the dog’s whole life.

Dr. Gaynor: We work on the presumption that early intervention helps put the critical dysfunction at bay. Veterinarians are masters at preventive medicine, and if we take that into account, we can presumably help prevent the severity of OA for a longer period of time, just like we help prevent diseases with vaccination.

Dr. Epstein: We need radical acceptance by veterinarians, then translate that to the owner. Vets need to accept the fact that this is inevitable for a subset of our patients—particularly if they have predispositions like being overweight. To radically accept it, embrace it, and change how you approach it in practice, that’s a transformative thing and is more difficult.

Dr. Robertson: At the end of this year, Lap of Love will have provided at-home euthanasia for 65,000 to 70,000 dogs. One of our biggest groups that we help in the home are large dogs with mobility issues because owners can’t get them in a car anymore. The data that we have is very, very sad; lots of dogs that we euthanize have not seen a veterinarian in the 12 to 18 months prior to the date they’re euthanized. We know that either they could have lived longer or at least lived a less uncomfortable life had they seen a veterinarian.

Dr. Tugel: A couple of you have mentioned the need for a mindset shift amongst veterinarians from thinking of OA as a disease of older dogs to instead recognizing it as primarily a young-dog disease. What data do we have to support this shift?

Dr. Lascelles: We’ve been running a study where we took a cohort of dogs between 8 months and 4 years of age in a first-opinion practice and screened them with full-body radiographs and multiple measurement tools. Based on those data, of the 125 dogs between 8 months and 4 years of age, the overall prevalence of radiographic OA was around 40%. About half of those had obvious clinical signs based on veterinary assessment, and in a smaller fraction, owners recognized clinical signs. We have an educational opportunity.

Based on those data, of the 125 dogs between 8 months and 4 years of age, the overall prevalence of radiographic OA was around 40%.

Dr. Gaynor: Wow. That’s even higher than I would have predicted for dogs that young. Were these all breeds? Small breeds, large breeds?

Dr. Lascelles: Yes. Breeds were across the spectrum and breeds you would expect in a first-opinion practice in North Carolina.

Dr. Tugel: What do you recommend to general practitioners looking to radically accept canine OA as a young-dog disease and incorporate COAST as a proactive screening and staging tool?

Dr. Epstein: Basic COAST staging can be done in the exam room in just a moment or 2, literally. And that message can drive acceptance and utility of it. It’s a staging tool, like IRIS for chronic kidney disease in cats. My view is to make it as simple and fast as possible, and that’s what will increase its adoption in clinical practice. I, for one, am a true believer.

Dr. Gaynor: When I talk about using COAST, I have boiled it down to history because that’s where we get necessary information from the owner. Then, just like COAST says, “evaluate the dog, and evaluate the joint,” which is pretty easy from a veterinary perspective. As soon as I realized that COAST was an important component of OA management, we plugged it in to the practice management system, so if you’re going to complete the form, you have to complete the COAST part.

Dr. Epstein: If practice software systems can be adapted to prompt COAST scoring, it would make acceptance and utility of the tool infinitely more than it is now.

Dr. Lascelles: You won’t see these data for a while, but with a very novel objective measure, which is being evaluated, out of all the tools—CBPI, LOAD, HCPI—COAST most accurately ranked dogs in terms of degree of disability. So, there’s no doubt about that; it’s very good.

Dr. Tugel: Can you comment on the benefit of proactive screening with COAST?

Dr. Epstein: The most obvious benefit to me is really in those COAST stage 1 dogs. If you have a Labrador puppy or a Rottweiler puppy, you start to have a conversation that's much different in terms of tone and emphasis than you might once have. First of all, "Do not let this dog get overweight, ever. It's hugely important that you never let her get overweight, period." It gets into picking the right kind of dog food— large-breed foods, joint foods, and then eventually supplementations or EPA-rich diets. So, it’s different in terms of scope and tone when you have a COAST 1 dog. That’s really where I know it’s made a big difference in my approach to these conversations.

Dr. Medina: I think the key target for COAST screening is general practitioners that are seeing dogs as puppies, introducing the concept early so veterinarians can recognize it early, intervene early, and educate early. When dogs come in for a particular lameness or mobility issue, we’re a little bit behind the ball. If we could have caught them earlier, we could have had that conversation then. And if we have that conversation with them early, it’s not a new conversation that the owner is hearing when the dog is lame and having to make a quick decision on treatment; they’ve had that information already in the back of their mind, they’ve been looking for signs, and when the signs truly happen, they’re more aware and will come in sooner and hopefully intervene sooner.

Dr. Tugel: What are your typical recommendations for at-risk, COAST stage 1 dogs?

Dr. Epstein: It’s weight optimization, chief amongst all others, and exercise and omega-3 fatty acids. But it can’t just be any old omega-3 fatty acid. It’s an EPA-rich diet specifically; I think that’s where the evidence lies.

Dr. Gaynor: A lot of people don’t want to change their dog’s diet for a hundred different reasons, so I don’t even recommend joint diets anymore. If someone’s interested in it, then we’ll go down that path, but with EPA supplements, they can feed their dog whatever they want and still get this potential benefit.

It can’t just be any old omega-3 fatty acid. It’s an EPA-rich diet specifically; I think that’s where the evidence lies.

Dr. Lascelles: One should certainly consider surgery if there’s a risk factor that is amenable to surgical correction, with the idea of limiting OA in the future. Exercise helps with weight management, so that makes a lot of sense. COAST stage 1 dogs are clinically normal but have risk factors. So, I think it’s important to make clear that the recommendation for omega-3s is a lifestyle modification, hopefully a modifier of the future, as opposed to a treatment.

Dr. Robertson: The problem with supplements is they’re not an FDA-approved drug where you have data and a dose and dose interval. It could be off the shelf at a big box store, or it could be a highly effective, veterinary-specific product. I agree with Dr. Lascelles; it can get people into the kind of mindset that they could then avoid a proven drug, like nonsteroidals, which are necessary once a dog has moved beyond COAST stage 1 into clinical OA.

Dr. Tugel: Do you have any tips or tools that you recommend to help veterinarians be successful in communicating about weight management?

Dr. Gaynor: We’re going to use weight optimization not only as a therapy but hopefully as a preventive measure. With every young patient I see, we talk about this, and I use the graph from the Purina Lifelong Labrador Retriever Study that shows the incidence of hip osteoarthritis in slightly overweight dogs versus slightly underweight dogs (see Suggested Reading). I think that’s a powerful tool to show veterinarians and owners. I use that a lot.

Dr. Medina: I use the Hill’s program where it does the morphometric measurements and body fat index (see Suggested Reading). I like it because it gives the client a nice visual graph of where they are currently, what their anticipated weight should be, and how long it’s going to take to get them to reach that goal.

Dr. Tugel: Let’s discuss treatment recommendations for dogs with clinical OA. Starting with COAST stage 2 (mild OA), what are your evidence-based treatment recommendations?

Dr. Gaynor: We use Galliprant very early in these dogs. If we haven’t started an omega-3, high-EPA supplement already, I would recommend it here. I think PSGAG also belongs early in the course of treatment. It is probably more beneficial as part of our early interventions than our later interventions. And, of course, I don’t do it all at once; we usually start with something, will re-evaluate, and add something else as needed.**

Dr. Lascelles: To me, because there are clinical signs, that early stage of mild OA warrants an effective analgesic, which are the nonsteroidals, and then getting them in the correct direction as far as lifestyle goes—exercise, diet optimization, and caloric intake. I would also consider the need for targeted intra-articular therapy if there is only 1 joint involved or as an adjunct to systemic treatment. I think, as we move up the COAST stages, at any time, a systemic treatment could be swapped out for intra-articular or intra-articular could be used as an adjunct.

Dr. Medina: I agree. I recommend those things as well. Because of my rehab background, I usually evaluate if there are any physical limitations in the patient’s home that we can address. If there are, then we can make some modifications or talk about how they might be necessary down the road. We’ll also talk about appropriate exercise for a dog with OA, how being sedentary is not ideal, and that they should be doing routine low to moderate impact exercise to ensure they are staying as fit as possible and that their joint health is maintained as long as possible.

Dr. Tugel: What might you say to practitioners who are hesitant to utilize NSAIDs in younger dogs with mild OA and prefer to reserve them for later in the disease course?

Dr. Medina: This is an inflammatory condition; NSAIDs are going to be our number one choice of defense for something that has an inflammatory component. I think we’re lucky Galliprant came to the market because it has a different mode of action than previously available NSAIDs. It blocks OA pain and inflammation without disrupting production of prostaglandins.

I think we’re lucky Galliprant came to the market because it has a different mode of action than previously available NSAIDs. It blocks OA pain and inflammation without disrupting production of prostaglandins.

Dr. Lascelles: Over the years, I’ve found it’s been really difficult to take a younger dog and talk to an owner about the long-term use of a nonsteroidal—whether COX-inhibiting or non-COX–inhibiting. If you say to someone with a 2-year-old dog, “Your dog needs to be on nonsteroidals for his life,” my experience is that they just don’t buy into that. But if you say, “Let’s try an effective, aggressive therapeutic for a few months, then taper the drug; you may be able to take it off the drug, and the dog may remain well if you have these other lifestyle changes,” you are much more likely to get buy-in, and owners are more likely to work with you as a team. With this approach, once the owner has seen the improvement, they then buy into the idea of managing their pet. That’s been my clinical experience.

Dr. Tugel: What does your typical NSAID prescription look like for a dog you’ve diagnosed for the first time with mild OA (COAST stage 2)?

Dr. Robertson: I agree with what Dr. Lascelles said about using an aggressive full dose at the start.

Dr. Epstein: My approach is evaluating how often they are showing clinical signs. A dog showing clinical signs in COAST stage 2 or even 3 may not need an anti-inflammatory agent every day for the rest of its life. If the signs are short-lived or intermittent, we might use Galliprant for just 2 weeks and evaluate from there, possibly withdrawing the drug and reassessing. But the more and the longer they are symptomatic, the more likely they are to develop a maladaptive pain component. In those patients, I will prescribe for a minimum of 2 to 3 months, and it sounds like you might taper the dose then, is that correct, Dr. Lascelles?

Dr. Lascelles: Yes, or space out the dosing intervals.

Dr. Gaynor: My approach is pretty aggressive. I start them on daily treatment for 4 to 5 weeks—partly because the disease is waxing and waning, and if they’re in the trough of their pain, they’re going to look great, potentially even before the drug takes effect. So, I like them to go through some waxing and waning, and I recheck them in a month. Then, if they’re doing well, they have a 3-month recheck. So now we’re 4 months into it and I re-evaluate what we need to do to manage this patient. It could truly be that we might taper the dosing. I don’t do this all the time, but sometimes I try to find the lowest effective dose on a daily basis. So, there’s a 1-month interval, and there’s a 3-month interval for me. And if they pass the 3-month interval and we decide not to make any changes, then they go to a 6-month interval. But, as they become stage 3 and stage 4 dogs, they’re seeing me every month for quite a while before we dare go out to 3 months without an assessment. Just like any disease, assess, treat, reassess—I take that very seriously.

Dr. Lascelles: I agree. It’s a shorter initial trial. Is there efficacy, is it tolerated? Once that’s determined, then I’m looking at 3 months before I start making other recommendations. Either I’ll take the dose down or bring in other treatments; I can go so many different directions. It takes a while to build up muscle mass. Three months is what I think is a clinically appropriate initial period. Then I re-evaluate. For the younger dogs, I’m looking to get them off the nonsteroidal, if I can, or to the lowest effective dose, and for dogs that are COAST 3 or 4, possibly bringing in additional treatments. So, it’s a process of re-evaluating as time goes along, in terms of patient response, owner ability to instigate treatments or inability to pay, all of those things.

Dr. Tugel: What factors play into your choice of NSAID for dogs with OA?

Dr. Gaynor: My rationale for choosing Galliprant specifically is that it targets the EP4 receptor, which is very responsible for inflammation associated with osteoarthritis. By targeting the EP4 receptor, as opposed to just being a COX inhibitor, we allow all those other prostanoids that would be inhibited to still do what they’re supposed to be doing, pretty much at full function. So, as we target the EP4 receptor, blocking it, we can get the anti-inflammatory effect without the undesirable effect of blocking production of prostanoids like traditional NSAIDs do. That’s the goal.

Dr. Lascelles: Galliprant offers a targeted approach. If you think about the rationale, EP receptors other than EP4 are involved in pain and inflammation in other species, but in dogs, EP4 is the most highly expressed of the EP receptors. So, it appears to be a very appropriate target for a targeted mechanism of action, thereby leaving all the other prostaglandins alone.

Dr. Tugel: What are your evidence-based treatment recommendations for COAST stage 3 (moderate OA)?

Dr. Gaynor: My take on these stage 3 dogs is that they’re starting to develop some muscle atrophy; they’ve got some inability to do what they normally do, so a lot of these dogs are now coming to see me. They have oftentimes come with a history of being on an NSAID and it “doesn’t work anymore.” So, this is where I implement amantadine for 21 days to turn off the NMDA receptors, and now I get adamant about a dog having to be on their NSAID pretty much every single day because they’ve already shown their propensity for maladaptive pain. They may be getting something else too, but my recommendation at this point is NSAIDs every single day.

Dr. Lascelles: For the dogs in stage 3, I start with the general recommendations for stage 2, but the exercise becomes more thoughtful/therapeutic, and the expectation is that the nonsteroidal is going to need to be continued daily. We’re probably not going to get away from that. And then I go with Dr. Gaynor’s recommendation. I’ll be thinking, add in 1 extra drug, that’s usually amantadine, then probably 1 other nondrug therapy, and that’s where you’ve got so many to choose from.

Dr. Robertson: It’s unusual for a dog at that stage to be on monotherapy, including nonpharmacologic stuff. It’s likely that COAST stage 3 dogs need to be on multiple medications.**

At this stage, I also recommend some of the intra-articular injections. In my practice, that is specifically going to be PRP; I’m optimistic about what I’m seeing in the literature.

Dr. Epstein: In COAST stage 3, we will also use adjunctive pain-modifying medications in addition to daily NSAIDs. I probably gravitate to gabapentin because it’s on our shelf. We sometimes add amantadine in, or use it instead, particularly if the dog is having any kind of neuro issue. At this stage, I also recommend some of the intra-articular injections. In my practice, that is specifically going to be PRP; I’m optimistic about what I’m seeing in the literature. I could do stem cells as well, but that’s quite an expensive process, and it currently requires 2 procedures—one to collect and harvest and the other to inject.

Dr. Medina: I agree with Dr. Gaynor and Dr. Epstein regarding gabapentin, amantadine, PRP, and stem cells; those are the intra-articular procedures I’m doing as well, and definitely PSGAG. At this stage, I’m also talking about rehab, shockwave, and other therapeutic modalities along that route to help with pain management and mobility.

Dr. Epstein: Yes, I wanted to mention the rehab period. We advise therapeutic exercises, and we could definitely use better resources to help lay out the plan for owners to do this kind of thing at home.

Dr. Medina: I think that brings up a good point from the client perspective. Obviously, with my OA cases, they don’t come to me every week for the rest of their lives. That would be unaffordable for them. So, I think it is more reasonable to try to set them up with an exercise program that they can do a few times a week that will help them with their mobility; it’s something that can definitely be implemented in general practice. It’s just trying to kind of understand what physical limitations that dog has and what exercises might be helpful. I’m working with a group on writing a book that’s geared toward general practitioners regarding OA, and that is going to be one of the chapters—guidelines on home-care exercises. You can set them up for success with the home-care program, and then when they come for their follow-ups, make sure that they’re able to do those exercises.

Dr. Tugel: What are your evidence-based treatment recommendations for COAST stage 4 dogs (severe OA)?

Dr. Lascelles: For me, it becomes more complex, more urgent, and you have to engage the owner in the management. If you’re going to do it effectively, there’s a greater burden on the owners. They’re either going in for rehab, performing therapeutic exercise in the home environment, or managing a dog that is less able to be mobile. In addition to that, they have to stay on top of medications and coming in for other nondrug therapy.

Dr. Robertson: You kind of start tapping out their budgets. There’s a financial budget, but there’s also a time budget. If it’s a big dog, there’s a physical budget; for example, elderly people can’t deal with that mobility-impaired big dog. Then there’s the emotional budget of looking after these pets when they get to that stage. It doesn’t need to be the financial one that’s tapped out for people to make a decision to stop.

I rarely feel more like a veterinarian than when I’m able to see these pets and hold them back—and the owners too—from that emotional edge and give them back their dog in ways that are surprising to them.

Dr. Epstein: I look at these dogs with a great deal of optimism, because the owners are almost pre-grieving. They can kind of see the end coming, and their expectations can sometimes be so low that it’s super easy to intervene and, often in a cost-effective manner, restore these dogs to a degree of mobility and comfort that the owners would never have dreamed of. These are great opportunities; I rarely feel more like a veterinarian than when I’m able to see these pets and hold them back—and the owners too—from that emotional edge and give them back their dog in ways that are surprising to them. There are a few other modalities that I will pull out of the hat at this point. One of them is the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, like duloxetine or venlafaxine. These are not expensive. You can get the generic without difficulty. They’re generally very safe. These dogs with their age and chronic pain may well have— I find it hard to believe that they don’t—elements of the same kind of clinical depression that a comorbid person with chronic pain may have. We will begin to do some of these other modalities Dr. Lascelles was talking about in stage 3 that can be done at home. The Assisi LOOP is one, the pulse electromagnetic field. We do have acupuncture in our practice, and if they have not started it yet, even though it does require that pet to come in, we’ll certainly be advising it at that point. It’s better to have started earlier, but these are the kinds of things we bring in if they haven’t been brought up already.

Dr. Lascelles: I like your perspective, Dr. Epstein. We often think of treatment as being stepped, but many times, we see these stage 4s come in, nothing’s been done, and you’re absolutely right. Start simply, and you can make a dramatic difference. I think our approach shouldn’t be to try and make these dogs normal because you probably can’t, and I think that’s where a number of people go wrong.

Dr. Epstein: Yes, I think a lot of these pet owners are happy if the dog can get up to go outside and engage with them more and maybe hop on the couch when it hasn’t hopped on the couch in 2 years.

Dr. Robertson: There is so much scientific data on the impact of social support and less stressful environments that help pain. For rats in pain, they exercise them and give them friendly cage mates, and their brain starts to go back to normal and their behavior changes. There’s no doubt that a dog in a happy home is less likely to have as many emotional components of pain as one in a shelter where they’re isolated with no social interaction. I think we forget the impact of that on pain—the parts of the brain that interpret pain and psychological stuff are the same in many ways.

Galliprant® (grapiprant tablets) Indication

Galliprant® (grapiprant tablets) is indicated for the control of pain and inflammation associated with osteoarthritis in dogs.

Important Safety Information

Not for use in humans. For use in dogs only. Keep this and all medications out of reach of children and pets. Store out of reach of dogs and other pets in a secured location in order to prevent accidental ingestion or overdose. Do not use in dogs that have a hypersensitivity to grapiprant. If Galliprant is used long term, appropriate monitoring is recommended. Concomitant use of Galliprant with other anti-inflammatory drugs, such as COX-inhibiting NSAIDs or corticosteroids, should be avoided. Concurrent use with other anti-inflammatory drugs or protein-bound drugs has not been studied. The safe use of Galliprant has not been evaluated in dogs younger than 9 months of age and less than 8 lbs (3.6 kg), dogs used for breeding, pregnant or lactating dogs, or dogs with cardiac disease. The most common adverse reactions were vomiting, diarrhea, decreased appetite, and lethargy. Please see full prescribing information for more.

**The use of Galliprant in combination with other therapies has not been evaluated. See important safety information.