Congenital Hydrocephalus

Mark Troxel, DVM, DACVIM (Neurology), Massachusetts Veterinary Referral Hospital, Woburn, Massachusetts

Hydrocephalus is enlargement of the ventricular system resulting from increased CSF production, inadequate CSF drainage, obstruction of CSF outflow, or reduced brain parenchyma volume (eg, age-related brain atrophy, infarction).1,2

Although hydrocephalus can also occur as an acquired disorder, this discussion highlights the congenital form. Congenital hydrocephalus is most often obstructive (ie, noncommunicating). Most cases result from fusion of the rostral colliculi in the midbrain causing obstruction of the mesencephalic aqueduct, with secondary enlargement of the ventricular system rostral to the midbrain.3 Congenital hydrocephalus in cats can be caused by prenatal treatment with griseofulvin4 in queens or intrauterine exposure to feline panleukopenia virus.5

Related Article: The Critical Neonate: Under 4 Weeks of Age

Signalment

Congenital hydrocephalus is most commonly identified in young (2-3 months of age) toy-breed dogs.2,6 The condition is much less common in cats.

Dog breeds commonly affected with congenital hydrocephalus9

Boston Terrier

Cairn Terrier

Chihuahua

English Bulldog

Lhasa Apso

Maltese

Pekingese

Pomeranian

Pug

Toy Poodle

Yorkshire Terrier

Clinical Signs

Common clinical signs include a dome-shaped head (Figure 1) with a persistent fontanelle, behavior problems (particularly difficult house-training), blindness, and seizures.1,2 Bilateral ventrolateral strabismus (ie, a type of divergent strabismus, Figure 2; characterized by the “setting sun” sign) may be seen if both eyes are affected.2 Patients may appear mentally dull to stuporous. Gait abnormalities (eg, head pressing, dysmetria, ataxia, pacing, circling) are also common.1,2

Pug with divergent strabismus caused by congenital hydrocephalus

Diagnosis

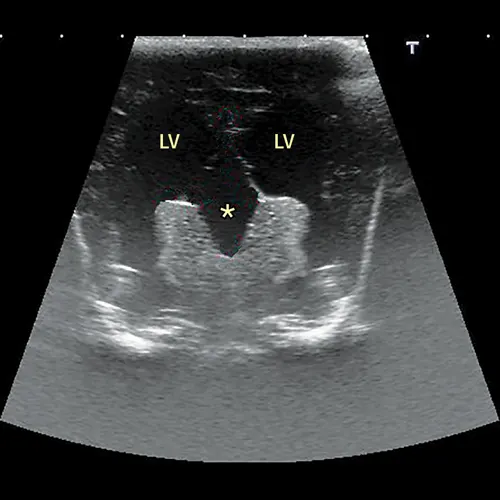

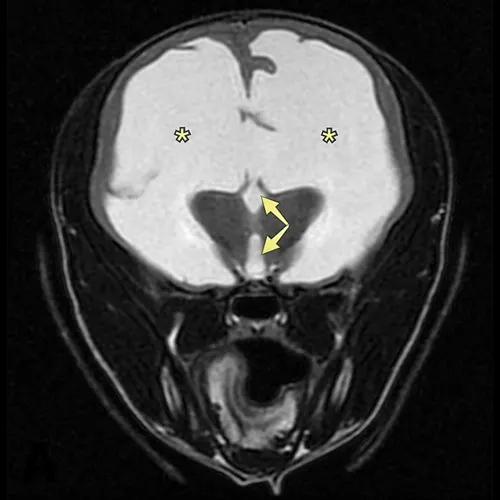

Ultrasonography of the fontanelle, temporal bone, or foramen magnum can be used for diagnosis in patients with a persistent fontanelle (Figure 3).7 Advanced imaging, with MRI preferable to CT (Figure 4), is required to fully characterize the condition and rule out concurrent disorders.

Transverse ultrasound of the brain obtained through a persistent fontanelle demonstrating enlargement of the lateral ventricles (LV) and a supracollicular collection of CSF (asterisk)

Transverse MRI at the level of the thalamus demonstrating severe enlargement of the lateral ventricles (asterisks) and third ventricle (arrows)

Related Article: Alternative Anticonvulsants for Dogs & Cats

Treatment

Medical management—which is not curative—is typically started first to alleviate acute clinical signs or deterioration. It may be the only treatment pursued when surgery is not an option. The duration of improvement may be relatively short (weeks to months) in moderately-to-severely affected patients; however, some patients with mild-to-moderate clinical signs can be managed long-term. The primary goal of medical management is to reduce CSF production and treat secondary clinical signs (eg, seizures). Options for reducing CSF production include 1 or more of the following: omeprazole (0.5-1.0 mg/kg PO once a day), furosemide (0.5-2.0 mg/kg PO once or twice a day), prednisone (0.25-0.5 mg/kg PO twice a day), and acetazolamide (10 mg/kg PO 3 times a day).1,2,8-10 Mannitol (0.5-1.0 g/kg IV over 15-20 minutes) may be needed for emergent patients. Omeprazole or furosemide may be used in mildly affected patients, with other medications added as needed. The author typically starts with prednisone. The goal of treatment is complete resolution of clinical signs, but often only partial remission is achieved. Once clinical signs are controlled or stabilized, the prednisone dose can be reduced every 1 to 2 weeks to the lowest effective dose, typically administered every other day, to maintain an acceptable quality of life.

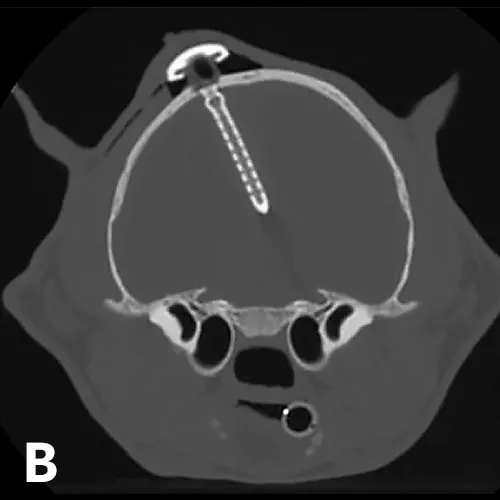

(A) Postoperative lateral radiograph and (B) transverse CT image showing a ventriculoperitoneal shunt placed in a cat. Although the well was not flush with the skull, the shunt appeared stable after the sutures were tightened. The cat did well after surgery. Images courtesy of Dr. Eric Glass, Red Bank Veterinary Hospital/Compassion First Pet Hospitals

Surgical placement of a shunt is preferred, especially when medical management fails.1,2,11,12 Because return to normal condition is uncommon following surgery, the goal of shunt placement is improvement in clinical signs. Most commonly used is a ventriculoperitoneal shunt (Figure 5), which diverts CSF from the ventricular system through a tube tunneled through the subcutaneous tissues to the abdomen, where CSF is then reabsorbed.1,2 Patients with mild-to-moderate hydrocephalus often do well postoperatively; patients with severe hydrocephalus and only a thin rim of brain parenchyma are at higher risk for postoperative complications.1,2,9 If too much CSF is removed (ie, overshunting), the brain parenchyma may collapse, resulting in tearing of meningeal vessels and hemorrhage.1,2 Other postoperative complications can include undershunting; shunt infection or obstruction, which may necessitate replacement; and/or seizures.1,2

Prognosis

The prognosis for congenital hydrocephalus is variable and depends on the degree of ventriculomegaly and presence of concurrent disease(s). No peer-reviewed scientific reports in the veterinary literature describe long-term prognosis for dogs treated medically, and few studies exist describing postoperative outcomes in small patient populations. In general, approximately 75% of dogs and cats have a successful outcome postoperatively.11,12

Related Article: Intermittent Pain & Scratching in a Cavalier King Charles Spaniel