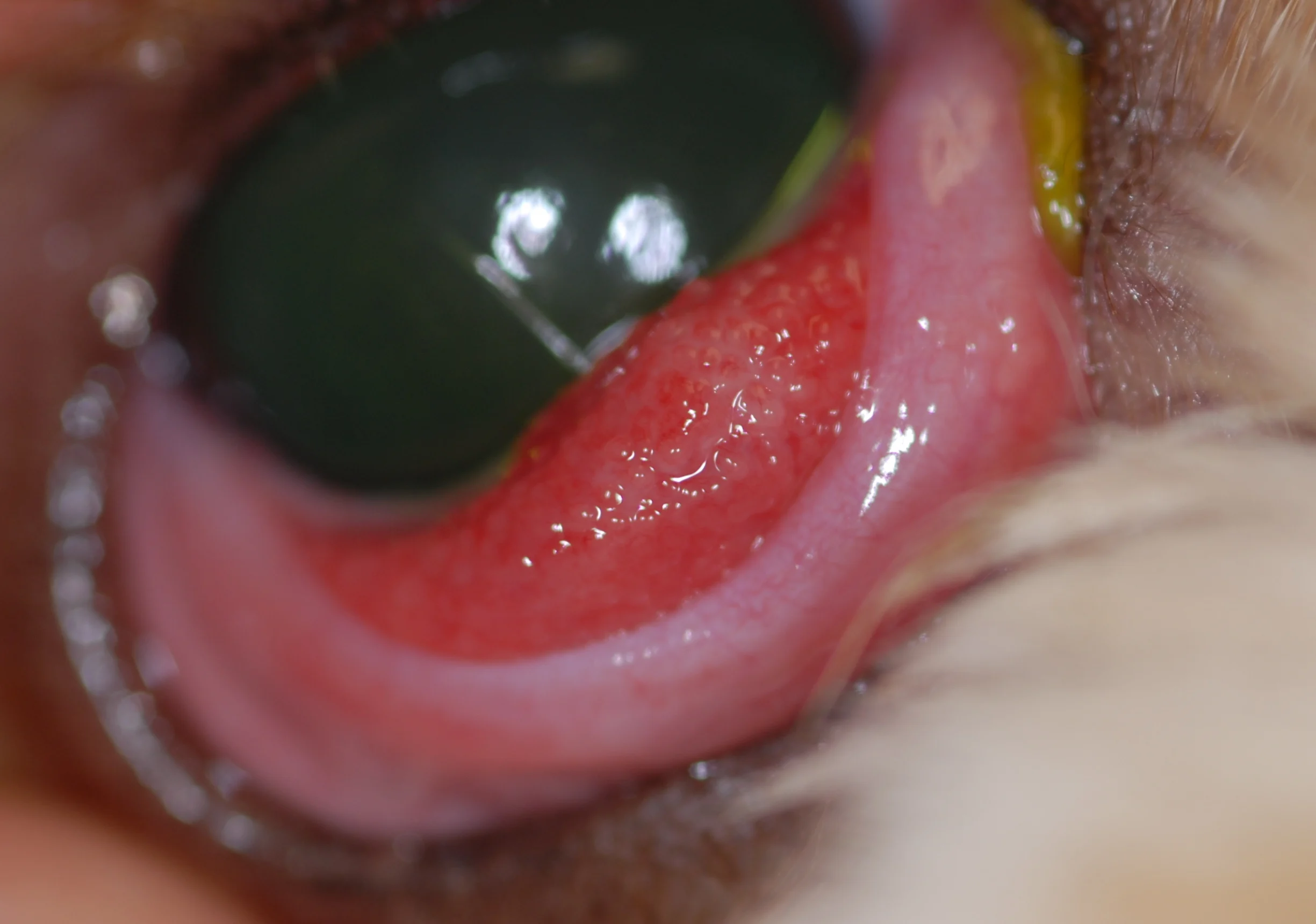

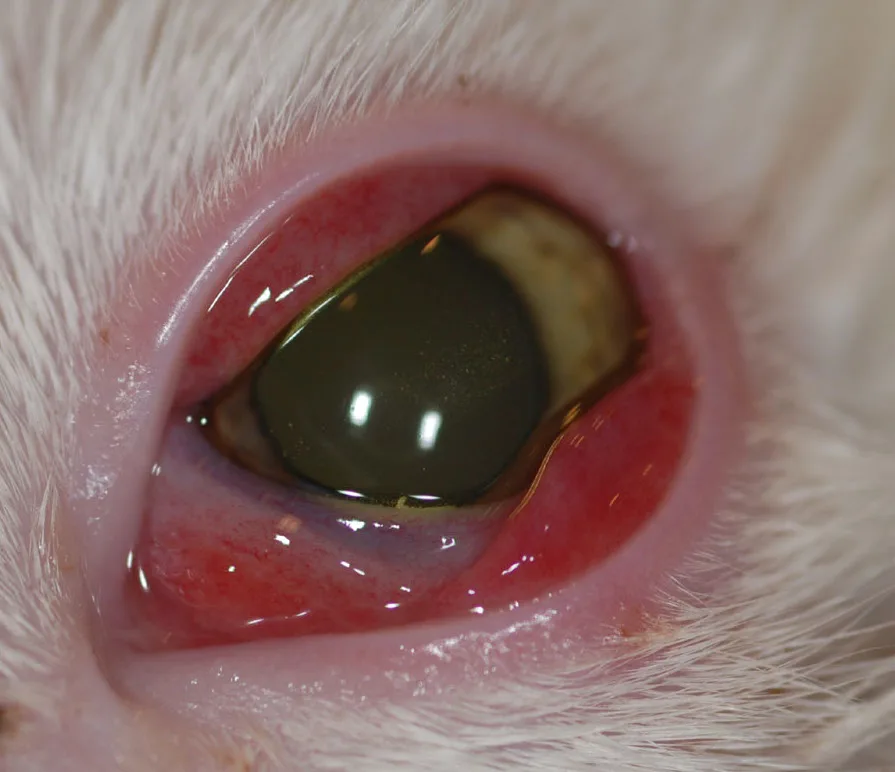

Conjunctivitis is inflammation of the conjunctiva (ie, mobile mucous membrane that lines the eyelids [palpebral] and surface of the globe [bulbar]) and can be primary (eg, allergic disease, immune-mediated inflammation, infectious disease process) or secondary (eg, to adnexal disease, tear film disorders, intraocular disease, systemic disease process).1 Clinical signs include conjunctival redness (eg, hyperemia; Figure 1), swelling, ocular discharge, and discomfort (eg, squinting or rubbing of the affected eye). Ulceration is less common but can occur following viral insult or injury to the conjunctiva.1

FIGURE 1 Marked conjunctival hyperemia and mucopurulent ocular discharge in a dog with conjunctivitis. Image courtesy of Louisiana State University

Primary conjunctivitis should be differentiated from other ocular disorders with ocular redness (eg, episcleritis, keratitis, uveitis, glaucoma) that would require additional diagnostic investigation and different management strategies. Most causes of conjunctivitis in cats should be considered infectious until proven otherwise2; causes in dogs are commonly noninfectious.

Disorders

Allergic Conjunctivitis

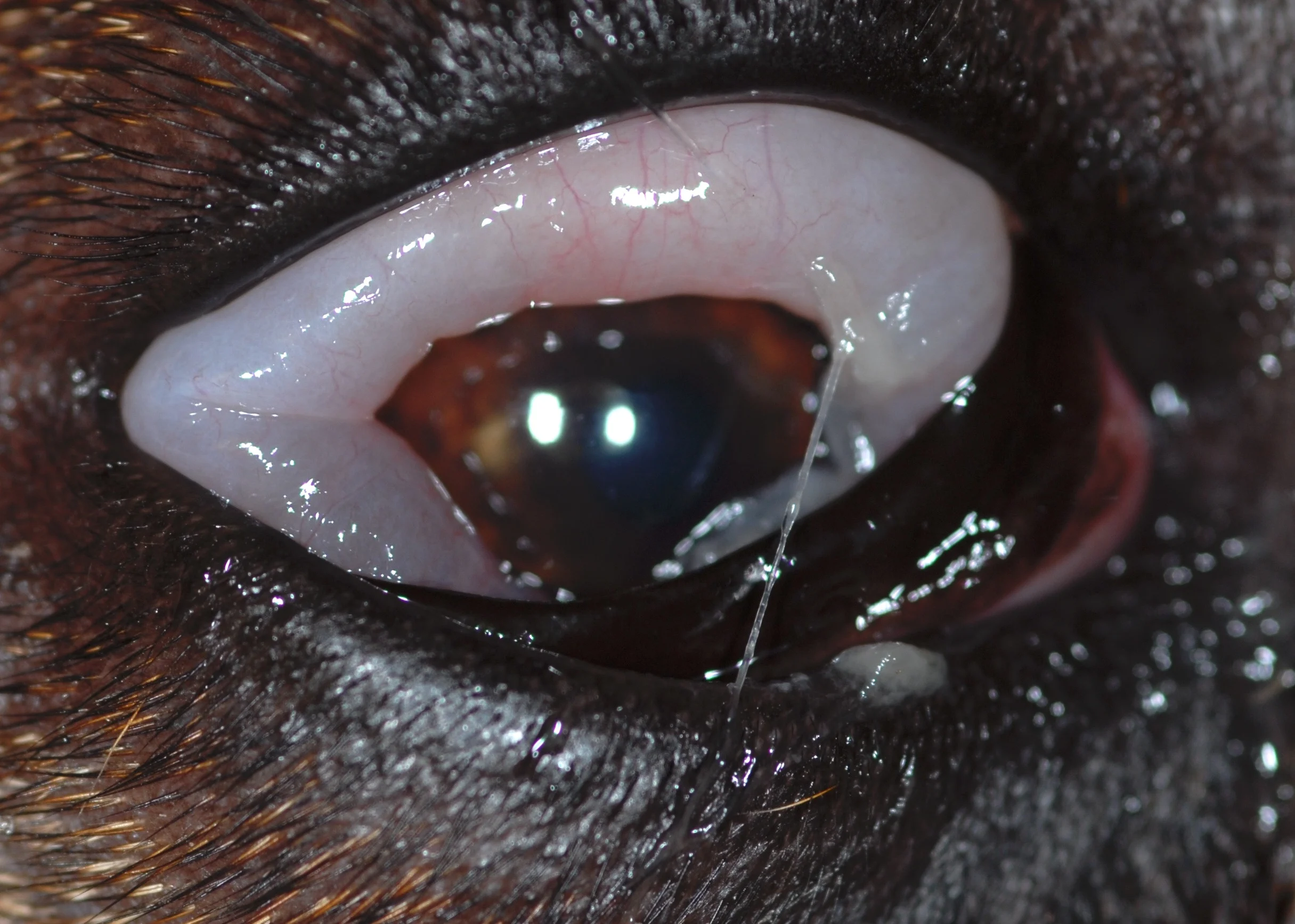

The most common cause of bilateral conjunctivitis in dogs is allergic disease (Figure 2). Periocular redness and alopecia are typical in patients with allergic conjunctivitis secondary to type 1 hypersensitivity reactions (eg, atopy).3 Lymphocytes and plasma cells can often be seen on conjunctival cytology.

Follicular conjunctivitis with prominent lymphoid follicles involving the posterior aspect of the third eyelid in a dog with allergic conjunctivitis. Image courtesy of Louisiana State University

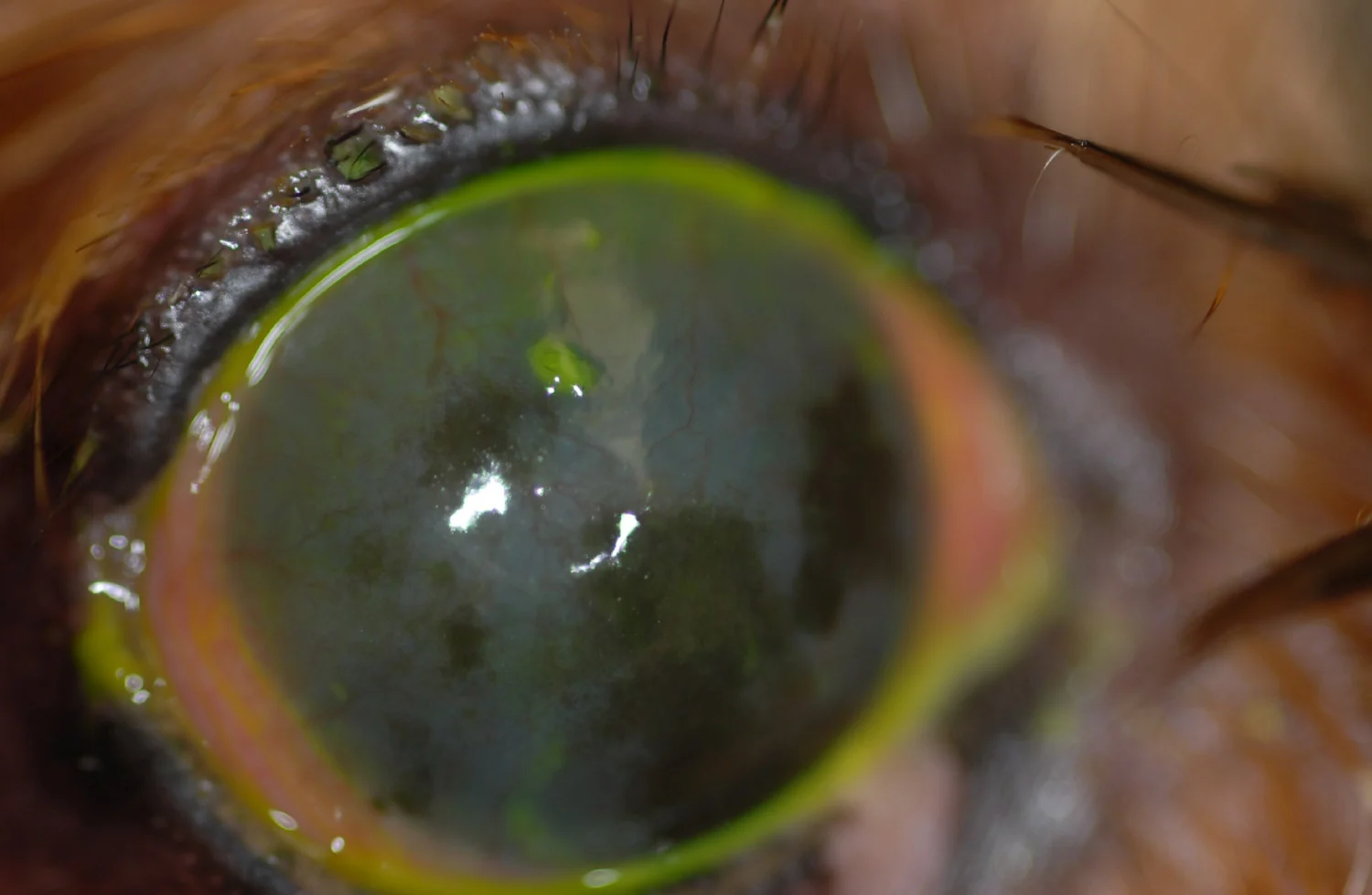

Acute, Bilateral Chemosis, & Blepharoedema

Acute, bilateral chemosis (Figure 3) and blepharoedema may be associated with an immediate-type hypersensitivity reaction mediated by histamine and immunoglobulin E.3 Reactions can be caused by contact allergy, vaccine reaction, or insect envenomation and should be treated with IM or IV short-acting corticosteroids and antihistamines, possibly in conjunction with topical corticosteroids.3 In patients with suspected ocular exposure to an irritating compound, the eye should be well irrigated with saline and stained with fluorescein; surface pH should also be monitored.

Extensive chemosis with significant swelling of the conjunctiva and relative lack of inflammation in the right eye of a dog following insect envenomation. Image courtesy of Louisiana State University

Eosinophilic Conjunctivitis

Nodular Granulomatous Episcleritis

Eosinophilic conjunctivitis is most common in cats. Feline herpesvirus (FHV)-1 may be an etiology for this disorder, but this has not been verified.2 Both the conjunctiva and cornea may be involved. Eosinophils and/or mast cells are present on conjunctival cytologic samples.

Primary inflammation of episclera (ie, connective tissue between the conjunctiva and sclera) is often immune-mediated, resulting in multiple fleshy pink to tan-colored nodules (Figure 4). Collies, cocker spaniels, and Shetland sheepdogs are overrepresented.4

Focal nodular mass in a dog with nodular granulomatous episcleritis. Image courtesy of Louisiana State University

Conjunctival Inflammation

The following medications control redness, discharge, pain, and inflammatory cell infiltrates that characterize conjunctivitis of any etiology. Topical treatment (ie, eye drops, ointment) is often sufficient for primary conjunctivitis because of disease distribution in the conjunctiva, ease of application, increased drug levels at the site of interest, and reduced risk for systemic adverse effects.

Conjunctival inflammation is primarily managed with topical steroids or NSAIDs, depending on conjunctivitis etiology and severity. Secondary forms of treatment include topical antihistamines, mast cell stabilizers, and vasoconstricting agents. Topical management options are described here.

Corticosteroids

Neomycin/polymyxin/hydrocortisone (1% suspension or ointment)

Neomycin/polymyxin/dexamethasone (0.1% suspension or ointment)

Prednisolone acetate (1% suspension)

Prednisolone sodium phosphate (1% suspension)

Topical corticosteroids affect the lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase pathways (reducing inflammatory mediators [ie, reducing swelling, redness, and pain]), are commonly used to treat inflammatory ocular surface disorders, and can be used in cases of noninfectious conjunctivitis.5

Dosage (Dogs, Cats)

One drop or one-quarter–inch strip ointment per affected eye

Frequency should be based on severity but is most commonly every 12 to 24 hours.

Key Points

Suspensions should be shaken well before application.

Prolonged contact time with ointment can result in higher levels of local drug delivery compared with suspensions.5

Hydrocortisone is a weak corticosteroid appropriate for treating mild conjunctivitis.5

Treatment should be continued for 2 to 3 days beyond resolution of clinical signs.

As most cases of feline conjunctivitis are primarily infectious, use of topical corticosteroids is not recommended.

Topical corticosteroids are contraindicated in patients with corneal ulceration and/or infectious conjunctivitis (cats).

Neomycin can cause local drug-related hypersensitivity reactions that result in increased ocular redness, discomfort, and blepharitis.1

Long-term use of topical corticosteroids can result in crystalline lipid corneal deposits.5

Topical corticosteroids can reduce the risk for adverse effects associated with systemic administration; however, systemic absorption can still occur with topical application.6

Anaphylaxis can occur rarely in cats following application of topical ocular medications; polymyxin B (in both triple antibiotic ointment and triple antibiotic with dexamethasone and polymyxin B sulfate with oxytetracycline hydrochloride) has been associated with anaphylaxis.7

Cats with eosinophilic conjunctivitis should initially be managed with topical prednisolone acetate products and monitored for corneal ulceration.

Patients with eosinophilic conjunctivitis often require long-term therapy tapered to the lowest level that controls clinical signs.2 Topical or systemic antiviral therapy may be required, and patients should be monitored for corneal ulceration. Additional management options (eg, topical cyclosporine, compounded topical megestrol acetate) may be required for refractory cases.2,8

Topical steroids can be used for nodular granulomatous episcleritis; evaluation by an ophthalmologist is recommended.

Ophthalmic NSAIDs

Diclofenac (0.1% solution)

Ketorolac (0.4%-0.5% solution)

Suprofen (1% solution)

Flurbiprofen (0.03% solution)

Bromfenac (0.07%-0.09% solution)

Nepafenac (0.1%-0.3% suspension)

Topical NSAIDs can reduce ocular surface inflammation, swelling, and pain associated with conjunctivitis.5 Topical application can reduce the risk for systemic adverse effects associated with oral and injectable NSAID therapy.

Dosage (Dogs, Cats)

One drop per affected eye

Frequency should be based on severity but is most commonly every 12 to 24 hours.

Key Points

Topical ophthalmic NSAIDs are nonselective COX inhibitors.5

Frequently used in patients with mild to moderate ocular inflammation

Local irritation may occur after topical application.

Caution should be used in patients with concurrent corneal ulceration, as NSAIDs may slow corneal epithelialization.9 Increased healing time in dogs with indolent corneal ulcers has been reported.10

Effect of topical NSAIDs on corneal sensitivity has been evaluated,11,12 as reduced sensitivity would be expected to delay corneal wound healing. Corneal sensitivity was not reduced in healthy, nonbrachycephalic dogs given topical diclofenac and flurbiprofen or in normal, domestic shorthair cats given diclofenac, ketorolac, or flurbiprofen.11,12

Caution should be used in patients with history of increased intraocular pressure, as a decrease in aqueous outflow has been reported; decrease in the efficacy of antiglaucoma therapy may occur.13-16

Can be used in patients with primary infectious conjunctivitis (eg, feline chlamydial conjunctivitis), in contrast to corticosteroids

Vasoconstrictors, Antihistamines, & Mast Cell Stabilizers

Naphazoline (OTC, alpha agonist)

Ketotifen fumarate (OTC, antihistamine/mast cell stabilizer)

Olopatadine hydrochloride (OTC, antihistamine/mast cell stabilizer)

Nedocromil (prescription, mast cell stabilizer)

Lodoxamide (prescription, mast cell stabilizer)

Topical vasoconstrictors, antihistamines, and mast cell stabilizers are alternative treatments for allergic conjunctivitis. Depending on the concentration, many prescription or over-the-counter (OTC) products can reduce ocular redness, irritation, and tearing secondary to surface allergies.

Dosage (Dogs, Cats)

One drop per affected eye

Frequency should be based on severity but is most commonly every 12 to 24 hours.

Key Points

Alternative option for some patients with allergic conjunctivitis

Efficacy and safety for the treatment of allergic conjunctivitis in dogs and cats have not been reported.

Many OTC eye drops (eg, ketotifen, olopatadine) contain antihistamines that also stabilize mast cells.

Topical vasoconstrictors reduce redness; however, chronic administration is not recommended, as chronic hypoxia of the ocular surface and increased long-term (rebound) clinical signs are possible.17

Tear Film Disorders

Immunomodulators that decrease inflammation in tear glands and lacrimomimetics that directly stimulate the glands are the primary classes of drugs that can improve tear production in patients with tear film disorders (Figure 5).

Corneal vascularization, fibrosis, and pigmentation secondary to chronic KCS in a dog with conjunctivitis and keratitis. Image courtesy of Louisiana State University

Immunomodulators

Cyclosporine & Tacrolimus

Cyclosporine and tacrolimus are T-cell activation inhibitors that reduce the inflammatory process in tear gland tissues and clinical signs associated with dry eye in most dogs with keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS).

Formulation

Cyclosporine 0.2% ophthalmic ointment FDA-approved for treatment of quantitative tear film disorders in dogs

Cyclosporine 1% to 2% compounded in an oil or aqueous-based solution

Tacrolimus 0.02% to 0.03% compounded in an oil or aqueous-based solution

Dosage (Dogs, Cats)

Topical ointment

One-quarter–inch strip ointment per affected eye every 12 hours

Compounded solution

One drop per affected eye every 12 hours

Key Points

Patients with initial Schirmer tear test results of 0 to 2 mm of wetting per minute have lower improvement in tear production.18

Improved tear production is only possible when there is some functional lacrimal glandular tissue (eg, chronic KCS, secondary glandular atrophy).19

Delayed effect (ie, several weeks to months) in increased tear production.18,20

Administration frequency may be increased to every 8 hours in severe cases and after minimal response (Schirmer tear test, <10 mm/minute) is documented following 3 weeks of treatment.21

Cyclosporine can be compounded as 1% to 2% solutions in corn oil, olive oil, or medium chain triglycerides for patients that do not show clinical improvement with 0.2% cyclosporine ointment.

Topical cyclosporine for humans contains a lower concentration (0.05%) and is not recommended for management of KCS in dogs.

Local irritation of the conjunctiva and eyelids is possible.

Studies evaluating the effect of long-term topical administration on systemic lymphocyte proliferation have variable results, but significant suppression of lymphocyte proliferation is unlikely.22,23

Long-term treatment with topical immunomodulating agents may cause predisposition to surface disease; infectious conjunctivitis and infectious keratitis have been reported.24

Chronic topical use has rarely been associated with superficial corneal squamous cell carcinoma in dogs; brachycephalic dogs are overrepresented.25

Combination compounded products with cyclosporine and tacrolimus may be beneficial in refractory cases.21

Cyclosporine can improve mucin production in dogs with qualitative tear disorders.26

Tear film disorders are less common in cats and generally secondary to chronic ocular surface disorders.

Cholinergics

Pilocarpine

Pilocarpine is a parasympathomimetic drug used to stimulate lacrimation. Use of this drug is primarily indicated in dogs with suspected neurogenic KCS; however, pilocarpine can also be used as adjunctive treatment in dogs with chronic KCS and a poor response to immunomodulating products.

Formulation

Commercially available as a topical 1% to 4% ophthalmic solution

Dosage (Dogs)

One drop topical pilocarpine (0.125%-0.25% diluted in lubricating eye drops) per affected eye every 12 hours.21

One drop ophthalmic solution (typically, 2% pilocarpine) per 22 lb (10 kg) body weight PO every 12 hours until signs of systemic toxicity are noted.21

Dose should be titrated based on patient body weight to the lowest amount that improves tear production and is systemically tolerated.

Patients weighing <22 lb (10 kg) can be given 1% pilocarpine PO titrated to the maximum tolerated dose; alternatively, topical solution can be administered.

Route of administration (ie, topical, oral) should be based on patient tolerance and baseline body weight.21,27

Key Points

Pilocarpine has a bitter flavor and should be given on a small piece of absorbent food to ensure the entire dose is consumed.

Oral dose should be increased by one drop per treatment each week, and the patient should be monitored for signs of systemic intolerance.

Systemic adverse effects of oral pilocarpine administration include excessive salivation, decreased appetite, diarrhea, and vomiting. The dose should immediately be reduced to the previous level that did not result in adverse effects; this is the maximum tolerated dose and should be continued daily as maintenance therapy.

Oral pilocarpine should be discontinued in patients with systemic effects that do not improve with dose reduction.

Ocular irritation (eg, squinting, redness, blepharitis, discharge) following topical application may occur, requiring discontinuation of the drug or addition of a topical anti-inflammatory agent.28

Bacterial Conjunctivitis

Etiologic differences between dogs and cats are important when considering therapy for bacterial conjunctivitis.

Dogs

Primary bacterial conjunctivitis is uncommon in dogs.1 Dogs have normal resident conjunctival flora, and bacteria can often be cultured from the conjunctiva.3 Secondary bacterial infections are more prevalent in dogs with tear film disorders or other disorders that compromise ocular surface health. Patients with a significant number of bacteria per high power field and neutrophils on conjunctival cytology may require short-term therapy while the underlying disorder (eg, atopy, KCS) is treated. Aerobic culture and susceptibility testing should be performed in patients with no improvement in clinical signs.

Routine broad-spectrum antibiotics for gram-positive bacterial conjunctival infections in dogs include topical neomycin, polymyxin B, bacitracin, gramicidin, and erythromycin. Therapy for gram-negative conjunctival infections includes topical neomycin, polymyxin B, bacitracin, gentamicin, tobramycin, and fluoroquinolones.3

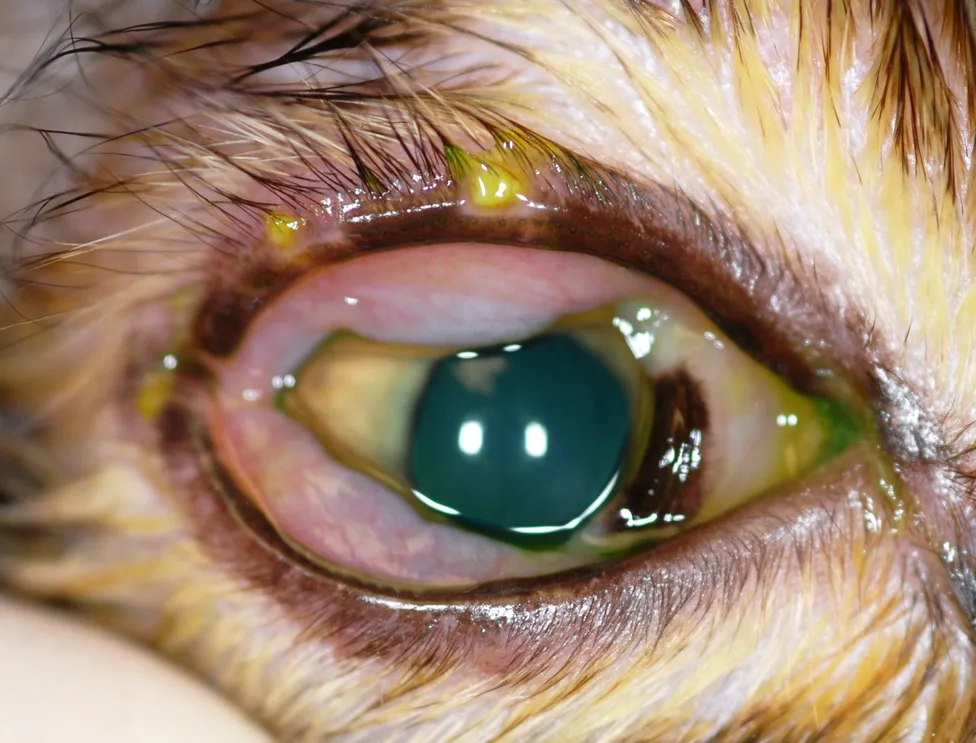

Cats

Primary bacterial conjunctivitis is common in cats. Important pathogens include Chlamydia felis (Figure 6), Mycoplasma spp, and Bordetella bronchiseptica. Treatment of the ocular surface alone is not curative due to presence of the organism in other systems (eg, respiratory, GI, and genitourinary tracts). Management should include topical and systemic therapy (eg, doxycycline, pradofloxacin, moxifloxacin) based on the pathogen responsible for disease, especially in patients presented with upper respiratory signs and positive via PCR.2,29

Blepharoconjunctivitis and serous ocular discharge in a cat with C felis infection; clinical signs were bilateral. Image courtesy of Louisiana State University

Ophthalmic Treatments

Formulation

Topical fluoroquinolones impact DNA synthesis, resulting in bactericidal activity.

0.3% ofloxacin (solution) or 0.3% ciprofloxacin (solution or ointment)

Second-generation fluoroquinolone

Strong activity against gram-negative bacteria, with effectiveness against some gram-positive infectious agents30

0.5% moxifloxacin (solution)

Fourth-generation fluoroquinolone

Stronger activity against gram-positive bacteria compared with second-generation fluoroquinolones; modification has resulted in reduced efficacy of fourth-generation fluoroquinolones against Pseudomonas spp.30

Topical macrolides are bacteriostatic agents that bind to the 50S bacterial ribosome subunit, inhibiting mRNA translation, and are capable of intracellular accumulation.30

0.5% erythromycin (ointment)

Topical tetracyclines are bacteriostatic agents that bind to the 30S bacterial ribosome subunit, inhibiting protein synthesis.30

Oxytetracycline/polymyxin B (ointment)

Dosage (Cats)

One drop or one-quarter–inch strip ointment per affected eye every 8 to 12 hours

Key Points

Common feline bacterial conjunctival pathogens are not susceptible to many topical antibiotic solutions or ointments (eg, neomycin, bacitracin, tobramycin, gentamicin).

Anaphylaxis in cats has been reported rarely following application of topical ocular medications; presence of polymyxin B (in both triple antibiotic ointment and polymyxin B sulfate oxytetracycline hydrochloride) was common in affected cats.7

Prophylactic treatment with topical fourth-generation fluoroquinolones (eg, moxifloxacin) is not recommended for routine or uncomplicated case management to reduce development of antibacterial resistance.30

Systemic Treatments (Cats)

Oral antibiotics include doxycycline, moxifloxacin, pradofloxacin, and amoxicillin/clavulanate.

Doxycycline (5-10 mg/kg PO every 12 hours) should be administered for 2 weeks for Mycoplasma spp infection and 3 to 4 weeks for C felis and B bronchiseptica infection. Cats with C felis infection should generally be treated for up to 2 weeks after clinical signs resolve.2,29,31

Marbofloxacin (2.75-5.5 PO every 24 hours for 2 weeks) has been used to treat Mycoplasma spp infection; however, the optimal duration of treatment is not known.31

Pradofloxacin (5-7.5 mg/kg PO every 24 hours) should be administered for 2 weeks for Mycoplasma spp infection and 6 weeks for C felis infection.29,31

Amoxicillin/clavulanate (12.5 mg/kg PO every 12 hours) should be administered for 4 weeks for C felis infection.29

Key Points

Systemic doxycycline should be avoided, if possible, in cats ≤4 weeks of age to prevent dental discoloration.2 Amoxicillin/clavulanate (12.5 mg/kg PO every 12 hours for 4 weeks) has been reported as an alternative in young kittens with C felis infection but is considered inferior.2,29

Oral doxycycline compounded solutions have a relatively short shelf life, and concentration could not be assured after 7 days in one study.32

Oral doxycycline tablets should be given with food or followed by a water bolus to reduce the risk for esophageal stricture.

Studies have shown oral azithromycin does not reliably eliminate C felis systemic infections.2,31

Infected cats should be isolated from other cats in the household, and living areas should be thoroughly cleaned to reduce reinfection rates.

Prophylactic, chronic use of topical and systemic antibiotics should be limited to discourage antibacterial resistance.33

Systemic enrofloxacin is not recommended in cats due to the risk for retinal toxicity.

Viral Conjunctivitis

FHV-1 and canine herpesvirus are the primary pathogens that cause viral conjunctivitis (Figure 7). There are no manufactured or approved antiviral drugs for treatment of veterinary ophthalmic viral infections.1,34 Herpetic viral infections are often associated with keratitis and conjunctivitis. FHV-1 is an alpha herpesvirus that causes upper respiratory tract infection, dermatitis, and ocular disease.34 Canine herpesvirus-1 is often self-limiting and infrequently requires antiviral therapy.1

Antiviral products are virostatic (ie, only act on a replicating virus) and herpetic viral infections can develop latency; antiviral drugs thus limit, but do not cure, disease.2,34 Safety and patient tolerance depend on how specifically the drug targets the virus without damaging host tissue. Therapy with an antiviral agent is generally not indicated in patients with mild disease and absence of corneal ulceration. Antivirals should be discontinued, not tapered, following resolution of clinical signs to reduce the risk for development of resistance.2

Blepharoconjunctivitis in a cat with FHV-1; clinical signs were unilateral and recurrent. Image courtesy of Louisiana State University

Idoxuridine

Idoxuridine is a thymidine nucleoside analogue that inhibits viral DNA synthesis.30,34

Formulation

Topical ophthalmic ointment or solution; compounded 0.1% or 0.5%

Dosage (Cats, Dogs)

One drop or one-quarter–inch strip ointment per affected eye every 4 to 6 hours

Key Points

Inhibition of DNA synthesis is not specific; therefore, there is an effect on virus and host cells.34

Due to nonspecific inhibition of DNA synthesis, topical application may result in adverse effects (toxicity to normal, noninfected cells), including punctate keratitis, corneal edema, reduced epithelialization rates, and corneal opacification.35

Should not be used systemically

Few studies have evaluated the effect of idoxuridine on cats with FHV-1 infections. In one study of a small number of cats treated every 4 to 6 hours, clinical improvement was only reported in a small percentage of subjects.36

Trifluridine

Trifluridine is a thymidine nucleoside analogue that inhibits DNA synthesis.30,34

Formulation

Topical 1% ophthalmic solution

Dosage (Cats, Dogs)

One drop per affected eye every 3 to 4 hours for 48 hours, then every 8 hours until clinical signs resolve1

Key Points

Should not be used systemically in veterinary patients

Penetrates the corneal epithelium well, increasing drug potency

Can have increased toxicity in normal tissues due to activation independent of viral kinase activity

Poor tolerability due to local irritation

Cidofovir

Cidofovir is a cytosine nucleoside analogue with a high affinity for viral DNA polymerase, resulting in reduced host toxicosis.34

Formulation

Topical ophthalmic solution; compounded 0.5% or 1%

Key Points

Long half-life that allows less-frequent application

Administration every 12 hours can reduce viral shedding and clinical signs.37

Local irritation possible; poorly tolerated in dogs1

Associated with nasolacrimal stenosis in humans; veterinary patients should therefore be monitored.34

Famciclovir

Famciclovir is the prodrug of penciclovir, which is a guanosine analogue that must be phosphorylated in multiple steps for activity. The first step in the phosphorylation process requires thymidine kinase (a viral-specific enzyme), which increases the margin of safety for the host.30,34

Formulation

125 mg and 250 mg commercial tablets

Compounded suspension

Dosage (Cats)

90 mg/kg PO every 12 hours based on tear and plasma concentrations34,38

Key Points

Antiviral therapy is generally reserved for patients with significant clinical signs and corneal ulceration.

Following oral administration, famciclovir is metabolized to penciclovir, which is the antiviral agent.

Low incidence of systemic adverse effects

GI effects are primarily reported in cats receiving treatment every 8 hours.2,34

Lysine

Amino acid lysine competes with arginine, which is necessary for viral replication.30,34

Dosage (Cats)

250 mg (kittens) to 500 mg (adults) PO every 12 hours2

Key Points

Use for management of FHV-1 is controversial due to conflicting study results.

In an experimental study, clinical signs following exposure to FHV-1 were reduced in treated cats but not eliminated compared with controls.39

In another study, oral lysine supplementation reduced viral reactivation and shedding in latently infected cats.40

In a study evaluating shelter cats, no effect of bolus treatment of lysine on the incidence of upper respiratory disease, time to onset of clinical signs, or the need for antibiotics was noted compared with controls.41

Lysine should be administered as an oral bolus, not a food additive. Decreased appetite, increased viral shedding, and clinical signs were identified in shelter cats given lysine as a food additive.42,43

Safe for oral administration

Arginine levels in the diet should not be restricted, as encephalopathy can develop.2,34

GI signs (eg, decreased appetite, vomiting) can develop.

Differences in study design and patient populations likely contribute to conflicting results in the literature.