Identifying & Managing Encephalitozoon cuniculi in Rabbits

Molly Varga Smith, BVetMed, DZooMed, MRCVS, Exotics Service at Rutland House Veterinary Hospital & Referral Center, St. Helens, United Kingdom

Clinical History & Signalment

Snowball, a 46-month-old, 2.75-lb (1.25-kg), neutered male dwarf lop rabbit, was presented to a referral clinic with a head tilt of 3 days’ duration, falling and stumbling while walking, anorexia, and failure to pass feces. He was current on vaccinations for myxomatosis and rabbit hemorrhagic disease 1 and 2, and his BCS was 2/5.1 Treatment at the referring clinic 3 days prior to current examination included dexamethasone (0.2 mg/kg IM once), enrofloxacin (10 mg/kg PO once daily), and fenbendazole (20 mg/kg PO once daily).

Snowball was part of a stable bonded pair with indoor and outdoor access; the companion rabbit was clinically normal.

Physical Examination

Snowball was quiet, alert, and responsive, demonstrating a right-sided head tilt of ≈30 degrees that worsened with manipulation and movement (Figure 1). Horizontal nystagmus with fast phase to the left was present intermittently. He was able to walk and hop with relative normalcy at slow speeds but stumbled and fell with a more rapid gait. Heart and respiratory rates were within normal limits. Gut sounds were reduced bilaterally. External ear canals appeared normal.

A rabbit with head tilt

Diagnostics

Neurologic examination was performed because of the head tilt; results were within normal limits2 except for the presence of head tilt, nystagmus, and reduced proprioception of the right thoracic limb.

Differential diagnoses included encephalitozoonosis3; middle and inner ear disease; toxoplasmosis; central brain lesion (eg, abscess, granuloma, tumor); lead toxicosis; cerebral larva migrans (eg, Baylisascaris procyonis [in endemic areas]); cerebrovascular accident; and viral (eg, rabies [in endemic areas], Herpesvirus cuniculi [leporid herpesvirus 4]), fungal, or bacterial meningitis. From a clinical and geographic perspective, the top differential diagnoses included middle and inner ear disease, encephalitozoonosis, lead toxicosis, toxoplasmosis, and intracranial space occupying lesion.

A blood sample was obtained for baseline serum chemistry profile and hematologic parameters and for Encephalitozoon cuniculi serology (immunoglobulin G and immunoglobulin M). Toxoplasma gondii titers and blood lead levels were also requested. Results suggested toxoplasmosis and lead intoxication could be ruled out, but encephalitozoonosis was still a possibility. A positive titer for E cuniculi did not prove a causative relationship, so further investigation was warranted.

Radiography and CT were considered to rule out middle and inner ear disease and intracranial lesions; however, both tests require sedation. As with other species (eg, dogs with gastric dilatation volvulus), rabbits presented in gut stasis (ie, anorexia and failure to pass feces) have an increased risk for death during sedation due to hemodynamic, acid–base, and electrolyte imbalances, all of which should be corrected prior to sedation if possible. Acetaminophen (20 mg/kg IV every 8 hours) was administered to address potential pain, prochlorperazine4 (0.5 mg/kg PO every 8 hours) was administered to improve vertigo, and cisapride (0.5 mg/kg PO every 8 hours) was administered to encourage gut motility. IV fluids and supported feedings were continued.

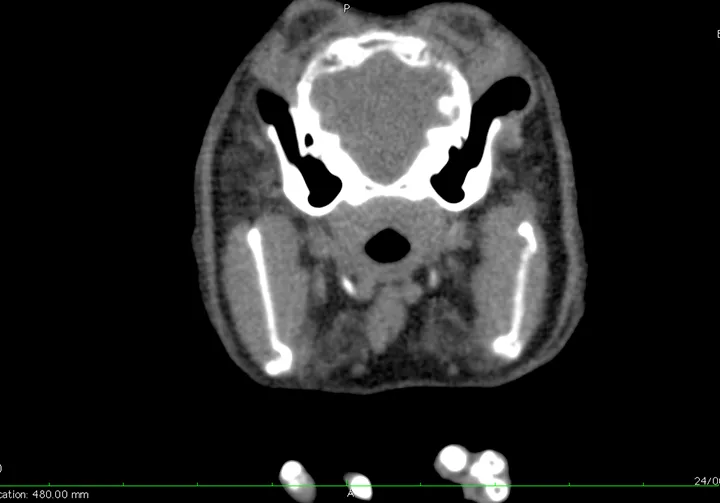

CT was performed after 2 days of supportive care because it is the most sensitive and specific method of diagnosing middle and inner ear disease and ruling out intracranial lesions.5 Results ruled out middle and inner ear disease5 and minimized suspicion for a central brain lesion (Figure 2). MRI is preferable for evaluation of soft tissue structures but was not available.

CT scan showing no evidence of middle or inner ear disease and no central brain lesion. Cerebrovascular accident is not likely visible except with hemorrhage.

E cuniculi serology was positive (1:1280) for immunoglobulin G, indicating likely active infection6,7; results for immunoglobulin M were negative (<1:40). C-reactive protein (4.34 mg/dL; normal, 0-2 mg/dL) was elevated.8 In combination with a positive E cuniculi titer, elevated C-reactive protein can improve the positive predictive value of this test. T gondii immunoglobulin G serology was 1:40, and blood lead was within normal limits (4 μg/dL; normal value not associated with clinical signs, <10 μg/dL).

Meningitis, cerebrovascular accident, and cerebral larva migrans could not be completely excluded; however, there was little evidence to support these as viable diagnoses in this patient.

DIAGNOSIS: ENCEPHALITOZOON CUNICULI

Treatment

Fenbendazole (20 mg/kg PO once daily) was continued for 28 days.9 Fenbendazole can be associated with adverse effects, including bone marrow suppression and aplastic anemia in rabbits, and careful monitoring is needed.

Dexamethasone administered at initial presentation, prior to referral, was not repeated. Rabbits are sensitive to the adverse effects of steroids, and white cell lysis, immunosuppression, and unmasking of underlying infections can be noted after steroid administration.10 Because a steroid had recently been administered, acetaminophen was selected for pain management in Snowball instead of an NSAID but was discontinued once middle and inner ear disease were ruled out.11,12 Acetaminophen is indicated when there is suspicion of intracranial pain.

Cisapride (0.5 mg/kg PO every 8 hours) was continued until Snowball was eating well and normally passing feces. The dose was then reduced over a period of 3 days and stopped once it was determined his appetite and feces production remained normal. Prochlorperazine was continued for 10 days until the head returned to a normal position. Meclizine has been used for this indication in areas where it is still available.

TREATMENT AT A GLANCE

Fenbendazole (20 mg/kg PO once daily for 28 days initially, then repeated for 9 days every 6 months)13

Dexamethasone (0.2 mg/kg IM once on acute presentation); use is controversial, as it may affect responsiveness to fenbendazole

Prochlorperazine (0.5 mg/kg PO every 8 hours) or meclizine (12 mg/kg PO once daily) for vertigo17

Supportive care, including fluid therapy and assisted feeding

The patient's environment should be assessed and steps taken to decrease risk for injury (eg, removal of high steps, provision of ramps and padded bedding/sleeping areas). Exercise and movement may lead to improved outcomes.16

Outcome

Once the medications were discontinued, Snowball experienced a mild deterioration in head position that improved over the following few weeks. On long-term follow-up, he remained clinically well, with only a slight head tilt that was more noticeable during periods of stress. Both Snowball and his bonded companion received 9-day courses of fenbendazole every 6 months in accordance with the drug manufacturer’s licensing.9,13

Discussion

E cuniculi is an obligate intracellular microsporidian parasite that affects many mammalian species (including dogs, humans, and rabbits). Infected patients shed infective spores in their urine. Organisms may be found in the gut, brain, and kidneys within 2 weeks of infection.14

Once suitable host cells are penetrated, the parasite proliferates (merogony), differentiates, and matures (sporogony), causing eventual rupture of the host cell and release of spores to complete the life cycle, which initiates the granulomatous response commonly associated with this disease.

In immunocompetent rabbits, infection remains latent and subclinical while the parasite and host immune response remain in balance.15 An immune response sufficient to clear the host of the organism would cause more damage to the host than the presence of small numbers of microsporidia.

Chronic granulomatous inflammation in host organs is likely responsible for the clinical signs (eg, CNS disease, renal disease, ocular disease) attributed to E cuniculi. Chronic inflammation results in the development of granulomatous lesions in target organs, primarily the kidneys and brain, although the liver may also be involved. Clinical signs are primarily associated with granulomatous meningoencephalitis or interstitial nephritis and fibrosis, notably vestibular disease and chronic renal failure.

E cuniculi has a variable prevalence (50%-75%) in rabbits.16 Most seropositive rabbits do not develop clinical encephalitozoonosis. In the author’s experience, it can be difficult to determine whether E cuniculi or another disease process is the cause in seropositive rabbits with compatible clinical signs (eg, head tilt, nystagmus, rolling), largely because many rabbits are seropositive with no clinical signs.

The prognosis for rabbits presented with acute head tilt is variable. Inner ear disease generally requires surgery, which is technically challenging and can result in postoperative complications (eg, facial nerve paralysis). Rabbits with confirmed encephalitozoonosis have a better prognosis with prompt and appropriate treatment. Most patients regain enough function to lead a relatively normal life. After appropriate treatment, many cases of acute head tilt improve; however, the patient may continue to display a small degree of head tilt, especially with stress or comorbid illness.

Take-Home Messages

Not all head tilts are caused by E cuniculi; therefore, robust diagnostic evaluation is necessary to rule out the likely differentials.16

Use of steroids in the acute presentation of head tilt is controversial, as they may significantly benefit the patient in the acute stages18 but negatively affect the patient’s response to subsequent treatment.19 Rabbits are sensitive to the effects of steroids and can experience white cell lysis, which can result in immunosuppression.10

E cuniculi titer levels and the degree of pathologic change observed in the brain are directly correlated, but neither the titer level nor the observed pathologic changes are correlated to the degree of clinical signs.8

C-reactive protein levels are correlated with clinical signs in patients with E cuniculi. C-reactive protein test can improve the positive predictive value when combined with titer levels.20

CT is more accurate (97%) in identifying middle and inner ear disease as compared with radiography (79%).21

Fenbendazole kills E cuniculi organisms in the body9 but does not treat the immediate clinical signs that are caused by granulomatous inflammation. Steroids (used cautiously on acute presentation), prochlorperazine,4 and fluids and assisted feedings can improve the patient’s well-being. Hematologic parameters should be monitored regularly in patients receiving fenbendazole because of the risk for bone marrow suppression and subsequent aplastic anemia.

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in October 2021 as “Head Tilt in a Rabbit.”