Hypokalemia in Feline Chronic Kidney Disease

Jessica M. Quimby, DVM, PhD, DACVIM, The Ohio State University

Hypokalemia is a common finding in cats with chronic kidney disease (CKD) with approximately 20-30% of cats affected.1,2 It is most common in IRIS stage 2 and 3 CKD patients and appears less common in stage 4 CKD cats due to markedly decreased glomerular filtration.3 Hypokalemia is typically less common in dogs with CKD which is likely due both to physiologic differences between dogs and cats as well as the fact that dogs typically have proteinuric CKD and are prescribed ace inhibitor therapy which can result in hyperkalemia. Practitioners should be aware of the clinical implications of hypokalemia in kidney disease, and identification and treatment of hypokalemic patients is recommended.

Regulation of electrolyte balance is a major physiologic function of the kidney. Potassium is freely filtered at the glomerulus and is then titrated further along the nephron via reabsorption and excretion depending on systemic requirements. The exact mechanism by which marked hypokalemia in feline CKD patients occurs is poorly understood. It is likely due to a combination of increased urinary loss due to polyuria resulting in less opportunity for reabsorption, inadequate dietary intake and activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. Potassium is the major intracellular cation and 95% of potassium is contained within muscle tissue.4 Chronic metabolic acidosis associated with CKD encourages intracellular potassium depletion due to intracellular influx of excess hydrogen ions and concomitant efflux of potassium.5 Therefore it is thought that serum potassium levels may not be representative of intracellular levels. Indeed normokalemic cats with CKD have been demonstrated to have lower muscle potassium levels than normal control cats.4

Once hypokalemia is present, clinical signs vary depending on the severity of the deficiency. Severe hypokalemia (< 2.5 mEq/L) may result in hypokalemic myopathy including cervical ventroflexion and plantigrade stance while Moderate hypokalemia (2.5-3.0 mEq/L) may result in muscle weakness, lethargy, inappetence and constipation.3 Mild hypokalemia may not be associated with obvious clinical signs, but it can be argued based on studies in humans that potential detrimental effects of mild hypokalemia in cats are poorly understood. In humans with kidney disease, hypokalemia <4 mEq/L is associated with increased risk for end stage renal disease and mortality.6,7 In rodent models, hypokalemia results in impaired renal angiogenesis, capillary loss and decreased vascular endothelial growth factor.8 In healthy adult cats, experimental diets inadequate in potassium have been shown to result in the development of renal dysfunction.9,10 However, hypokalemia has not been shown to be a risk factor for disease progression or outcome in CKD cats.11,12

Feline renal diets are supplemented with potassium and contain an average 0.7%-1.2% potassium on a dry matter basis, whereas canine renal diets are not supplemented (typically 0.4-0.8% dry matter basis).13 Since the introduction of potassium supplemented renal diets, clinical presentation of profound hypokalemia in cats eating these diets appears to be less common, but this has not been scientifically evaluated. Potassium supplementation is recommended in hypokalemic animals and the oral route is the safest and preferred route in stable patients. Based on the possible renal effects of hypokalemia and how questionably representative serum potassium is in the face of metabolic acidosis,4 some clinicians advocate prophylactic supplementation even when serum potassium is in the low normal range, with a goal of maintaining serum potassium levels above 4 mg/dL. However, the value of prophylactic potassium supplementation has not yet been established.

Potassium supplementation may be provided orally as potassium gluconate, (1-4 mEq per cat twice daily), or potassium citrate (40-75 mg/kg orally divided twice daily), to effect.14,15 Various forms of potassium supplements are available including pill, powder and gel. Potassium citrate has the added advantage of being an alkalinizing agent, however the degree to which this is effective for treatment of metabolic acidosis has not been evaluated. Potassium chloride is not recommended as an oral supplement because it is acidifying and unpalatable, but may be added to subcutaneous fluids at concentration up to 30 mEq/L (higher concentrations can be associated with irritation).5

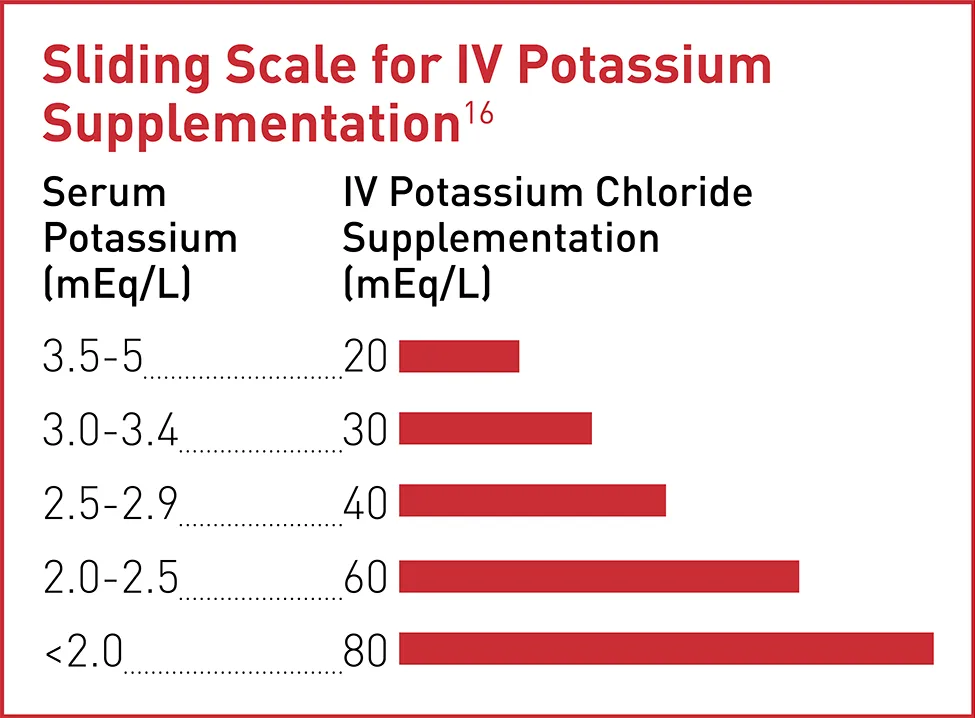

Severe hypokalemic myopathy can be seen in cats presenting in acute on chronic uremic crisis and is treated with hospitalization and supplementation of IV fluids with potassium chloride to normalize potassium before transitioning to oral supplementation in the home environment. While in hospital, electrolytes are rechecked frequently (q6-8 hours). Once normokalemia is achieved then IV supplementation is slowly decreased. Often if IV supplementation is suddenly stopped, hypokalemia will return and thus it may even be necessary to start oral supplementation while weaning IV supplementation to prevent relapse.

Previous literature has suggested that when hypokalemic myopathy is present it generally resolves within 1-5 days of initiation of oral or parenteral supplementation.3 After correction of hypokalemic myopathy, potassium supplementation is adjusted based both on clinical signs and serum potassium concentrations. In more stable and more mildly affected animals, serum potassium should be rechecked 7-10 days after initiating potassium supplementation and dosing titrated accordingly. It has not been assessed whether all hypokalemic CKD cats require long term potassium supplementation, but clinical impressions are that a majority of cats will.17 If hypokalemia appears particularly refractory to supplementation, medical conditions such as hyperaldosteronism should be considered.

In summary, the detrimental effect of hypokalemia on clinical well-being and kidney health in cats is likely underestimated. Cats with stable CKD as well as cats presenting in a uremic crisis should be routinely screened for hypokalemia so that this condition can be recognized and treated accordingly.

Key Takeaways