Ocular Manifestations of Systemic Disease

Kathern E. Myrna, DVM, MS, DACVO, University of Georgia

Understanding the connection between ocular clinical signs and systemic disease can help in identification of underlying disease processes and ensure ocular concerns are addressed when managing known disease that may affect the eyes.

Ophthalmologic examination can be performed using simple equipment or cell phone photography and should include a Schirmer tear test, fluorescein stain, and measurement of intraocular pressure. Retroillumination entails use of a flash photograph or a light source at arm-length distance from and eye level of the patient and can help distinguish cataracts from age-related nuclear sclerosis. True cataracts should block the glow from the tapetal reflection. In addition, retroillumination can be used to help identify the location of opacities (eg, corneal pigment, vitreal changes).

Using a bright, focal light source (eg, direct ophthalmoscope, transilluminator) in a dark room is necessary to assess the cornea and anterior chamber. Illumination of the eye from the front, from the side, and at a 45-degree angle provides the best opportunity for visualizing all defects. Sharply focusing the smallest circle or the slit beam on the direct ophthalmoscope can help determine whether the aqueous humor in the anterior chamber is clear. Similar to the brain, the eye is protected from systemic circulation through the blood–eye barrier (anterior and posterior). Uveitis results in a breakdown of this barrier, allowing inflammatory cells, protein, and organisms into the eye. This manifests as flare (protein), hyphema (blood), or hypopyon (WBCs) in the anterior chamber. Anterior uveitis is also associated with scleral injection, low intraocular pressure (<10 mm Hg), and miosis.

The fundus is the most challenging area to examine; dilation prior to examination typically improves visualization. Indirect ophthalmoscopy using a handheld lens enables a more complete view of the retina but can be difficult to perform, as it requires a handheld lens and precise alignment of the light, lens, and eye to get a full image. Direct examination with an ophthalmoscope or a panoptic ophthalmoscope can potentially help identify inflammation in the fundus.

The following images illustrate various diseases and conditions; many were diagnosed using the aforementioned techniques. Some findings are nonspecific, and others are suggestive of specific disease.

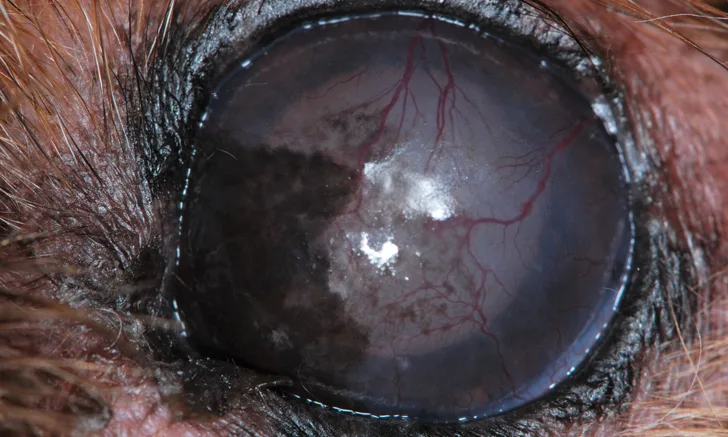

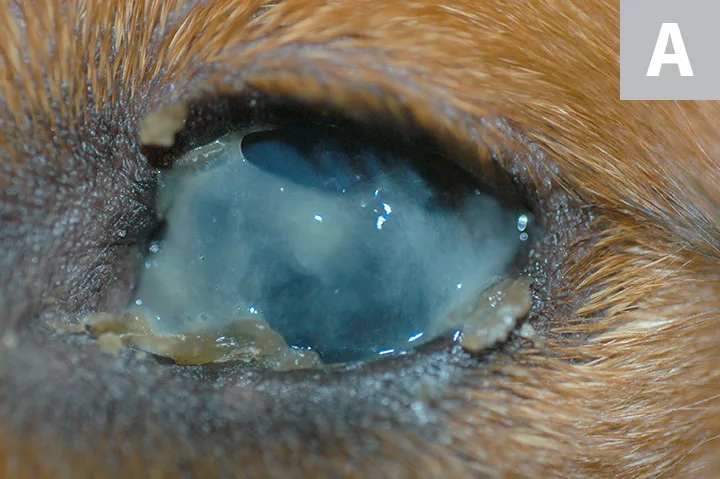

FIGURE 1A

Thick, tenacious mucoid discharge with crusting at the lid margins (A). The cornea is obscured by thick mucus but appears whitish-blue, indicating scarring of the cornea. This is typical of keratoconjunctivitis sicca (ie, dry eye), which is usually bilateral and autoimmune in origin. Patients with sulfa-drug toxicity can also have bilateral dry eye (Schirmer tear test <15 mm/minute). Corneal changes can be associated with chronic dry eye, including dull appearance of the eye surface, with corneal neovascularization and pigmentation (B). Unilateral dry eye with an onset later in life (>5 years of age) is most likely neurogenic in origin. A dry nare on the ipsilateral side is the most common sign of neurogenic dry eye (C). Although this can be idiopathic, it is also associated with inner ear disease and certain ear medications (eg, florfenicol/terbinafine/betamethasone acetate or florfenicol/terbinafine/mometasone furoate). A dry, crusty nostril associated with unilateral dry eye can be misclassified as primary nasal disease, and careful clinical consideration is indicated to avoid misdiagnosis. Neurogenic dry eye also requires specific therapy (ie, oral or topical pilocarpine), rather than cyclosporine or tacrolimus therapy, to replace the absent parasympathetic neurotransmitter.