Right lateral radiograph of a dog with moderate to severe pleural effusion

Pleural effusion can be common in dogs. Clinical signs include increased respiratory rate and effort, cyanosis, lethargy, and inappetence; mild cases may have minimal or no clinical signs. Physical examination findings may include decreased lung sounds, fever, heart murmur, pale mucous membranes, and shock, depending on the underlying etiology.

Imaging & Fluid Removal

Pleural effusion can be easily identified on radiographs (Figures 1 and 2) and ultrasound (Figure 3). In patients with respiratory distress, oxygen and sedation should be administered before standard aseptic, often ultrasound-guided, thoracocentesis is performed. Removal and collection of fluid can quickly improve oxygenation and ventilation and allow clinical investigation to determine the cause of effusion.

Ventrodorsal radiograph of a dog with mild to moderate pleural effusion

Right lateral radiograph of a dog with moderate to severe pleural effusion

Thoracic ultrasound of the left side of the chest in a dog with marked pleural effusion

Categorization

Effusions are typically categorized by protein concentration and cell count. Pure transudate is characterized by a low protein concentration (<2.5 g/dL), low cell count (<1,500 cells/µL), and clear or pale yellow color. Modified transudate is characterized by a protein concentration between 2.5 and 7.5 g/dL and cell count of 1 to 7,000/µL. Exudate is characterized by a high protein concentration (>3 g/dL), high cell count (>7,000 cells/µL), turbidity, and variable color.1 Packed-cell volume (PCV), total solids (TS) or refractometer reading, cytology, and paired triglycerides are often sufficient to classify effusions.

Using Light's criteria, additional qualifiers to differentiate exudate and transudate have been used in human and veterinary medicine (Table). Modified Light’s criteria can provide accurate classification of pleural effusion and its etiology but is not widely used in veterinary patients.2,3

Table: Light’s Criteria for Differentiating Exudates & Transudates

Following are the top causes of canine pleural effusion, according to the author.

1. Hemothorax

Hemothorax (ie, blood in the chest cavity; exudate) is diagnosed via comparison of PCV and TS of grossly sanguineous pleural fluid and peripheral blood. PCV of the pleural fluid is usually within 5% to 10% of peripheral blood hematocrit, and TS of the pleural fluid is within 10% to 20% percent of the total protein level of peripheral blood. High RBC and low WBC counts are typically found on cytologic examination of pleural fluid, similar to peripheral blood. In cases of subacute hemorrhage, collected blood may coagulate and/or clots may be identified on ultrasound; however, this may not occur if the patient is coagulopathic or fluid has already undergone fibrinolysis.

Coagulogram evaluation (eg, prothrombin and activated partial thromboplastin times, platelet count, viscoelastography, fibrin degradation products [specifically D-dimers]) is needed to diagnose coagulopathy. The most common causes of hemothorax are trauma and hypocoagulation from rodenticide ingestion, liver failure, acute traumatic coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia, and/or hemophilia. Additional differential diagnoses include migrating foreign body, parasitic infection, vascular or congenital abnormality, herniated organ, hemorrhage from neoplasia, lung lobe torsion, and complications from interventional techniques (eg, central catheterization).4-8 CT is often required to diagnose underlying etiologies not determined by patient history or coagulation testing. Blood may be collected aseptically and used for autologous blood transfusion if intravascular volume resuscitation is necessary (Figure 4).9

Aseptic pleurocentesis in a dog with hemothorax secondary to anticoagulant rodenticide toxicosis. Fluid determined to be pure blood may be administered as an autologous blood transfusion. Additional plasma and vitamin K1 therapy can also be provided.

2. Chylothorax

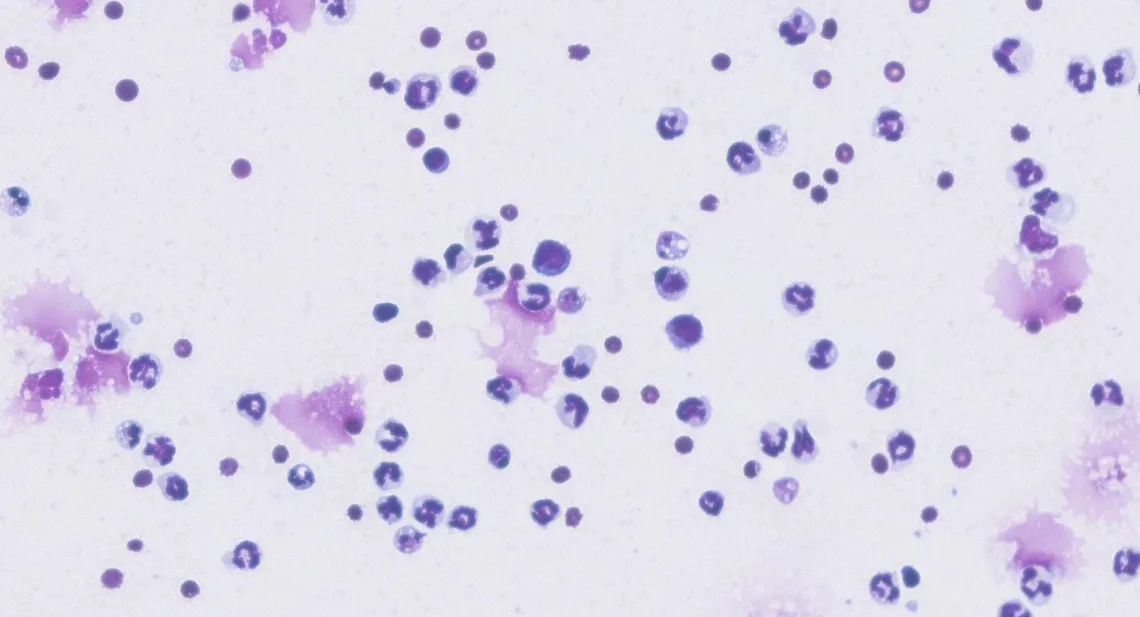

Chyle (ie, lymph fluid; exudate) accumulation in the chest can appear milky (Figure 5), yellow, or pink to red due to the presence of blood. Diagnosis can be made from a fluid:blood triglyceride ratio of >2. A high lymphocyte count can be seen on cytology (Figure 6) and should be reviewed by a clinical pathologist or via additional staining to differentiate neoplastic effusion. Chylothorax is often idiopathic but may be secondary to cardiac disease, lung lobe torsion, neoplasia, caval thrombosis, trauma to the thoracic duct, lymphangiectasia, or peritoneopericardial diaphragmatic hernia.10-13 Routine blood work and thoracic, cardiac, and abdominal imaging should be used to determine underlying etiologies. Surgical treatment of idiopathic chylothorax may be superior (success rate, 88%-94%) to medical management.14,15

Chylous pleural effusion (left) and pleural transudate from hydrothorax (right)

Photomicrograph of chylous pleural effusion. A large number of lymphocytes are visible. 40× magnification

3. Pyothorax

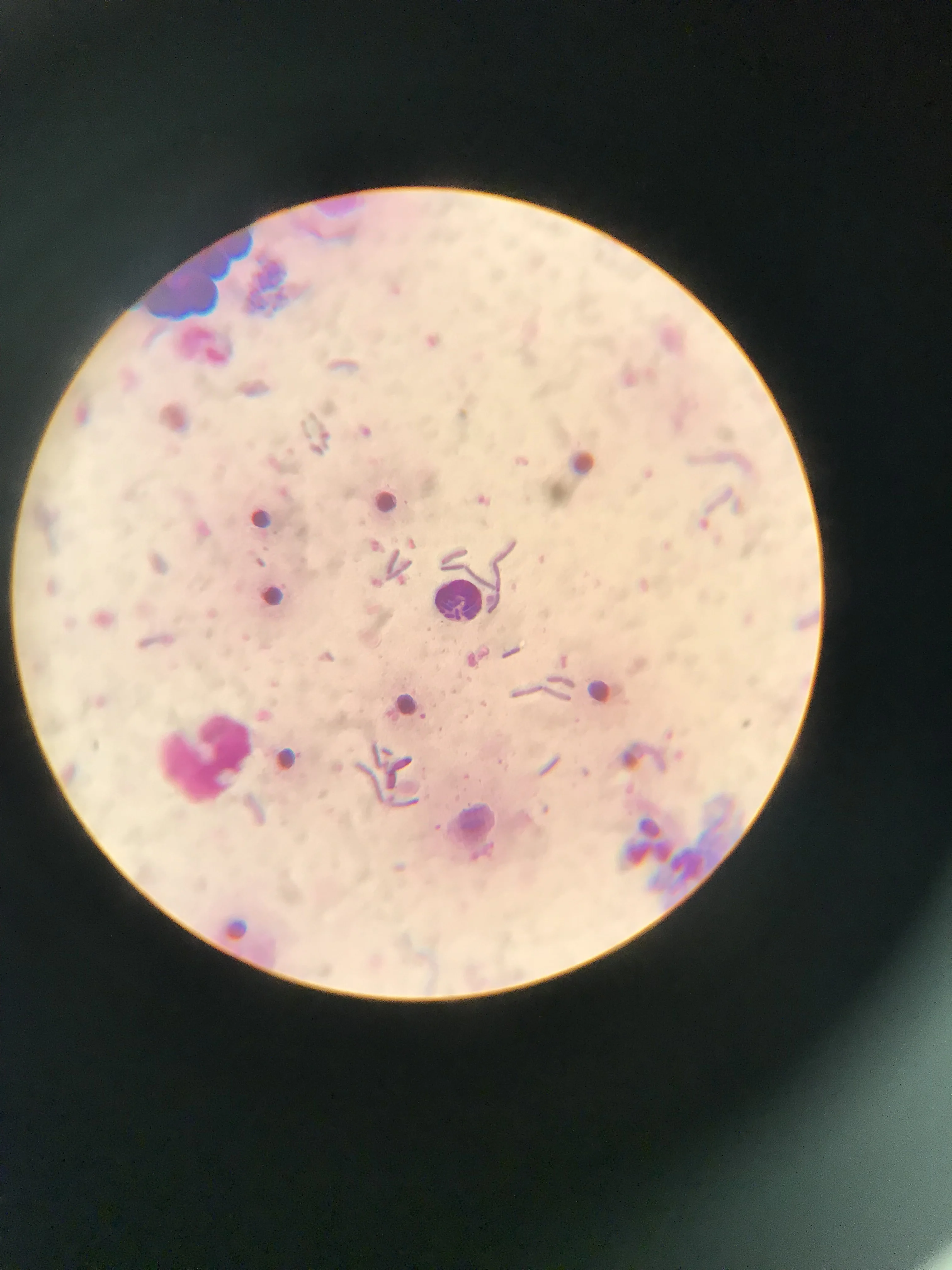

Pyothorax (ie, purulent pleuritis, empyema; exudate) can be due to a bacterial infection caused by a migrating foreign body, traumatic penetration of the chest cavity (including iatrogenic procedures), or extension of severe pneumonia.16 Pyothorax is often easy to identify as turbid fluid and may have a foul odor and/or contain flocculent material (Figure 7) or blood. High cell count and protein concentration, cytologic evidence of neutrophils (often with toxic change), and, commonly, bacteria are evident (Figures 8 and 9). Polymicrobial infection is common; treatment includes antibiotics (directed by aerobic and anaerobic culture and susceptibility testing), draining the pleural space with a thoracostomy tube or pleural catheter, lavage or surgery, and additional supportive care as needed.

Pyothorax; flocculant white material is visible within the fluid

Photomicrograph of fluid from a dog with pyothorax. Amorphous debris, central band neutrophils, and short chains of rod-shaped bacteria can be seen. 100× magnification

Photomicrograph of fluid from a dog with pyothorax. Numerous neutrophils, some macrophages, and minimal bacteria are present. 40× magnification

4. Nonseptic Pleural Effusions

Inflammatory and neoplastic effusions may be modified transudates or exudates. These fluids often have a grossly turbid appearance due to a high protein concentration and cell count and may be serosanguineous (Figure 10). Reactive mesothelial cells can share characteristics with neoplastic cells (Figure 11); cytologic evaluation by a clinical pathologist is therefore recommended.17 Nonseptic pleural effusions (Figure 12) may occur as a result of local or systemic disease (eg, neoplasia, mesothelioma [common], lung lobe torsion, trauma, pancreatitis, other severe systemic inflammation).18,19 Treatment should be based on underlying etiology, which may be determined via thoracic imaging (eg, postcentesis radiography, CT), abdominal ultrasonography, routine clinical pathology (including pancreatic lipase and urinalysis), and/or cytology or histopathology of masses.20-22

Neoplastic effusion from a dog

Photomicrograph of a neoplastic pleural effusion with cytologic characteristics of malignancy, including minimal inflammatory cells, a monomorphic cell population, large cells (compared with visible RBCs), a high nucleus:cytoplasmic ratio, anisocytosis, anisokaryosis, and occasional multinucleated cells. 40× magnification

Photomicrograph of an inflammatory, nonseptic, and nonneoplastic effusion. No infectious organisms are present. 100× magnification

5. Hydrothorax

Hydrothorax is a fluid with low protein concentration and low cell count (ie, transudate; Figure 13). Causes of transudates include decreased colloidal pressure (eg, protein-losing enteropathy, protein-losing nephropathy, hepatic synthetic failure, severe systemic illness) and increased hydrostatic pressure (eg, cardiac disease; IV fluid overload; vascular obstruction from neoplasia, embolism, or strictures).23 Thorough physical examination, routine blood work, urinalysis, and thoracic, cardiac, and abdominal imaging can help identify the underlying cause and direct treatment.

Photomicrograph of a pleural transudate. Few cells and minimal staining of background material can be seen, indicating a low protein concentration. 40× magnification

Listen to the Podcast

Dr. Linklater joined the podcast to dive deeper into his top causes of pleural effusion, including a bonus cause that didn't make the article.