Accessibility of ultrasonography has increased with advances in technology. Formal consultative ultrasonography requires extensive training to assess all imaging planes of organs and systems with an open-ended diagnostic approach. By contrast, veterinary point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) addresses patient-side, targeted, and evidence-based clinical questions in a rapid, noninvasive, and repeatable manner (Table).

Table: Formal Ultrasonography vs Point-of-Care Ultrasound

Following are the authors’ top reasons POCUS should be included in general practice.

1. Practicality

POCUS units can be brought to patients, allowing evaluation without disruption of patient management and care. For example, patients in unstable or critical condition do not need to be moved from an emergency resuscitation area or intensive care unit for POCUS evaluation.

POCUS results can complement visual assessment, palpation, and auscultation findings. Patients can be sonographically assessed during triage as part of the minimum emergency database while receiving resuscitation care (eg, supplemental oxygen, IV fluids, blood products), being housed in an oxygen cage, being hospitalized in a cage or run, or being held by the pet owner. POCUS is highly adaptable in the clinical setting, especially with advancement of laptop-style and handheld portable units (Figures 1 and 2).

Patient-side pleural space and lung POCUS during daily assessment in the intensive care unit. The patient is sitting upright, unrestrained, and receiving oxygen supplementation. The fur is parted, and alcohol is used as the coupling agent. Image courtesy of Katharina Lunde, DVM, MRCVS, GPCert(SAS)Orth

Examples of handheld ultrasound probes

Most imaging modalities, including radiography, MRI, and CT, require patient transportation to the machine, which can disrupt workflow and patient care and delay diagnosis and therapy, causing stress that can negatively impact patient and veterinary team well-being (see Improved Patient & Operator Well-Being). In addition, most imaging modalities often require sedation or anesthesia, may be cost prohibitive for owners, and involve risk for exposure to ionizing radiation.1 In comparison, POCUS is safe, rapid, and easily repeated; does not use radiation; requires minimal restraint; can be performed with the patient in a comfortable position; rarely requires sedation; and is often less expensive. POCUS allows real-time assessment of soft tissue structures and can therefore complement radiographic findings, which may not be able to identify or delineate changes to (or within) these structures.2

2. Minimal Training for Proficiency

Research in human medicine indicates standardized proficiency in POCUS can be achieved by completing a 2-day course that includes theory and hands-on experience and at least 50 POCUS examinations.3 Research in veterinary medicine suggests novice operators can answer binary (ie, yes or no) questions on abdominal, pleural space, lung, and cardiac POCUS with high accuracy following a brief (4- to 8-hour) hands-on training session, particularly when the session is followed by a longer period (up to 3 months) of clinical application.4-6 Some studies suggest a steeper learning curve for POCUS (eg, for diagnosis of pneumothorax), but research supports use of POCUS by nonspecialists to accurately diagnose abdominal, pleural space, cardiac, and vascular pathologies in cats and dogs.4,6-16

3. Streamlined Workflow

POCUS has a more streamlined application than formal consultative ultrasonography and is therefore user-friendly and rapid in general and emergency practice. POCUS can be performed in <5 minutes when examination focuses on clinically relevant questions with binary answers (eg, is pleural effusion present, is the number of B-lines increased; Video 1) rather than open-ended questions pertaining to multiple differential diagnoses (eg, what is causing dyspnea in this patient). Ruling out numerous differentials can be time-consuming and challenging without extensive sonography training, and open-ended questions can result in lengthy investigations without defined objectives that are difficult to address, especially for novice practitioners.

4. Multiple Clinical Applications

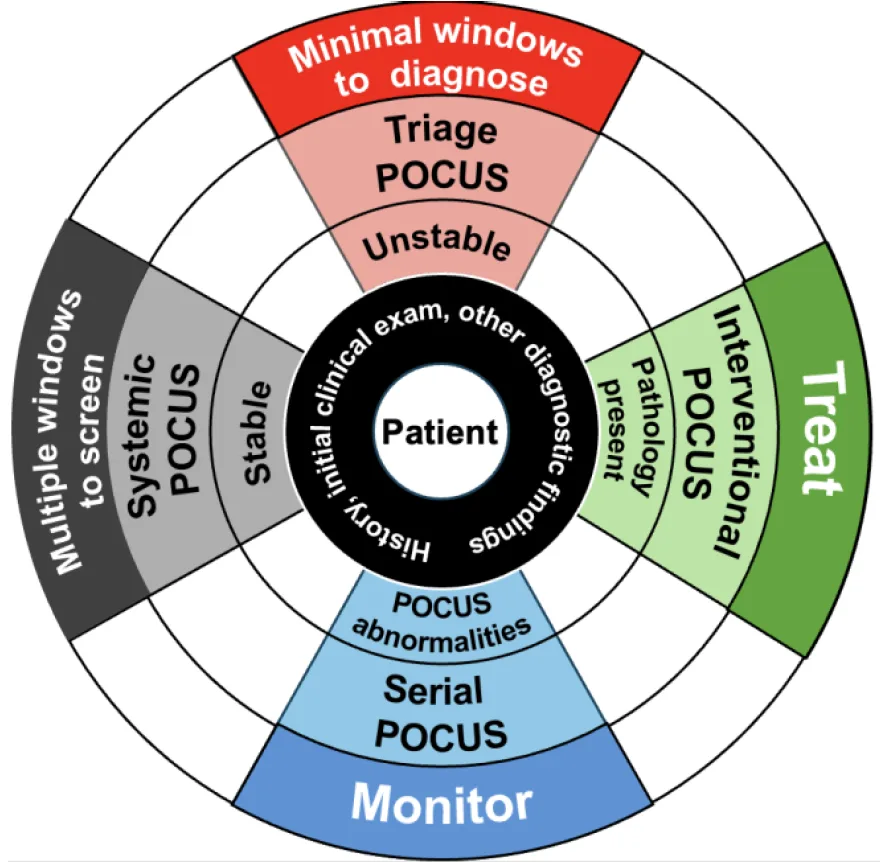

Applications of POCUS vary depending on the clinical situation and patient stability. A study in human medicine suggests POCUS should be performed following patient history and physical examination and before laboratory testing and further diagnostics in acutely ill patients.17 Depending on the clinical context and binary question, POCUS can emphasize targeted examination, trauma assessment, triage, tracking, treatment, or total assessment (see Six T’s of Point-of-Care Ultrasound, Figure 3).

Six T’s of Point-of-Care Ultrasound

Targeted examination

Examination of a specific organ or area of interest based on patient history, clinical findings, and clinical context

Example: Targeted sonographic evaluation of the kidneys—particularly the renal pelvis—during evaluation of a cat presented with a 3-day history of vomiting, anorexia, lethargy, and marked azotemia, as marked dilation of the renal pelvis would support diagnosis of pyelonephritis or ureteral obstruction

Trauma assessment

Assessment of trauma during diagnostic examination

Example: Rapid initial assessment of unstable patients with blunt or penetrating trauma for possible abdominal, pleural, or pericardial effusion; pulmonary contusions; pneumothorax; and/or pneumoperitoneum

Triage

Abbreviated examination that uses the minimum number of sonographic windows (ie, sites assessed with ultrasonography) to identify the most immediate life-threatening conditions

Example: Assessment of the subxiphoid or transthoracic parasternal windows for pericardial effusion in a collapsed dog that is agonal and has muffled heart sounds, weak pulses, and evidence of poor perfusion (ie, pale mucous membranes, prolonged capillary refill time)

Tracking

Serial evaluations to track progression and/or resolution of identified conditions and response to therapy (Video 2)

Example: Resolution of B-lines following furosemide administration in a patient with left-sided congestive heart failure

Treatment

Ultrasonography-guided interventions when pathology is identified or suspected

Example: Ultrasonography-guided local nerve blocks, abdominocentesis, thoracocentesis, or pericardiocentesis

Total assessment

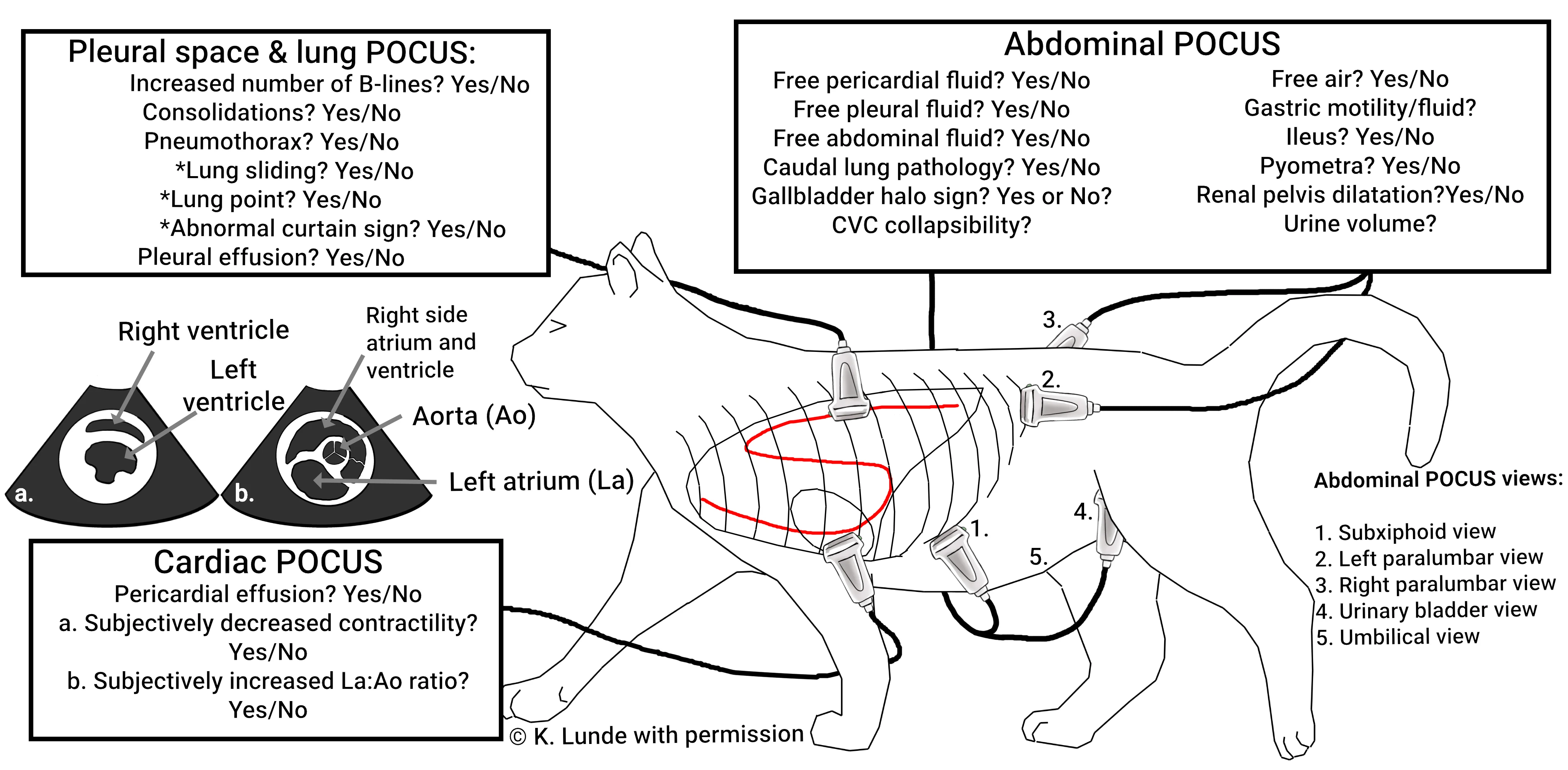

Systemic or multiorgan assessment using multiple sonographic windows to detect subclinical conditions and/or new developments with or without specialist assistance (Figure 4)

Can help rule out development of new problems prior to procedures, anesthesia, or discharge/service transfer

Often a baseline measure or part of comprehensive examination in adequately stable patients

Example: Abdominal, pleural space, lung, and cardiovascular POCUS during initial examination of patients presented to an emergency clinic and daily assessment of hospitalized patients

Illustration of how POCUS can be applied based on the likelihood of a problem and patient status. POCUS is patient centered; patient history, triage findings, other clinical findings, and diagnostics should be assessed first (black ring). If the patient is unstable, triage POCUS should be performed using the minimum number of sonographic windows necessary to identify and correct life-threatening conditions (red wedge). If pathology is identified on POCUS, ultrasonography-guided interventional procedures (eg, thoracocentesis, pericardiocentesis, abdominocentesis) may be indicated (green wedge). Abnormalities identified on POCUS can be followed serially for resolution or progression to help determine whether treatment is successful (blue wedge). If the patient is sufficiently stable for longer sonographic assessment, complete systemic POCUS can be performed (gray wedge). Image courtesy of Calgary VPOCUS Academy

5. Accuracy

POCUS is well documented in human and veterinary literature as an accurate diagnostic modality to detect pathology. A veterinary study comparing the original 2004 abdominal focused assessment with sonography for trauma protocol to CT for detection of free abdominal fluid found excellent agreement between the modalities.7 Another study suggests as little as 0.2 mL of free peritoneal air can be accurately diagnosed with ultrasonography, resulting in integration of pneumoperitoneum examination in POCUS.18 Ultrasound is reflected by air-filled lungs and cannot detect pathology >1 to 3 mm below the lung surface19; however, studies in human medicine indicate 95% of respiratory diseases that result in lung parenchymal changes can be detected at the lung surface using POCUS.20,21 Veterinary studies support the accuracy of POCUS to detect left-sided congestive heart failure, pulmonary contusions, pneumonia, pneumothorax, and pleural effusion in cats and dogs.21-38 Assessment of intravascular volume status via caudal vena cava changes, gall bladder wall edema, renal pelvic dilation, and left atrial enlargement have also been studied.12,13,39-46

Illustration of total POCUS (ie, cardiac, pleural space, lung, abdominal) in a cat, showing common binary response questions asked for each sonographic window. Pleural space and lung POCUS is performed bilaterally using internal ultrasonography-guided landmarks as the borders and includes the subxiphoid view. Presence of pneumothorax can be assessed by asking 3 key binary questions (asterisks). The pleural space can be further examined by turning the probe 45 degrees in the ventral aspect to search for smaller fluid pockets (not shown). Cardiac POCUS is performed on the right side of the patient in both long and short (a and b) axes. (For illustrative purposes, the left side of the cat is shown because pleural and lung POCUS is assessed bilaterally, but for cardiac POCUS, the probe would be placed over the heart on the right side.) Abdominal POCUS is performed with 4 or 5 views, depending on patient size and the clinical question. Findings should be evaluated within the clinical context of the case. Asking the correct binary questions is key. This figure does not represent all questions and nuances that POCUS can assess and is only provided for reference. Image courtesy of Katharina Lunde, DVM, MRCVS, GPCert(SAS)Orth

6. Improved Patient & Operator Well-Being

POCUS can be performed simultaneously with stabilization, other diagnostic tests, and therapy, which can expedite patient care by providing information not attainable through physical examination, increase support for a diagnosis, and improve patient comfort by avoiding delays in treatment. Studies in human medicine demonstrate increased diagnostic confidence in clinicians who incorporate POCUS into routine examinations.47 POCUS is dynamic, providing real-time feedback that is key for acquisition and interpretation of information. For example, POCUS can increase confidence when performing centesis by confirming presence of pathology (eg, free fluid or air) and providing guidance to ensure samples are obtained from the correct location.

Conclusion

POCUS is practical and adaptable, allowing examination without disrupting patient care. Results can increase diagnostic confidence, thereby reducing patient and operator stress. POCUS has multiple applications and is a reliable diagnostic modality that has excellent agreement with other types of imaging. Research suggests proficiency can be achieved quickly—even by novice operators. Rapid development and numerous benefits of POCUS technology highlight the importance of incorporating this tool in daily clinical practice.

For a review of the top limitations of POCUS in general practice, see the accompanying article.