Thrombocytosis, an increase in circulating platelets to >500-600 × 103/µL, can be due to a myeloproliferative disorder but is most often a nonspecific finding that is either physiologic or reactive (ie, secondary to an underlying disease).

Ask the Expert: Why do platelets appear elevated for no obvious reason in some apparently healthy patients?

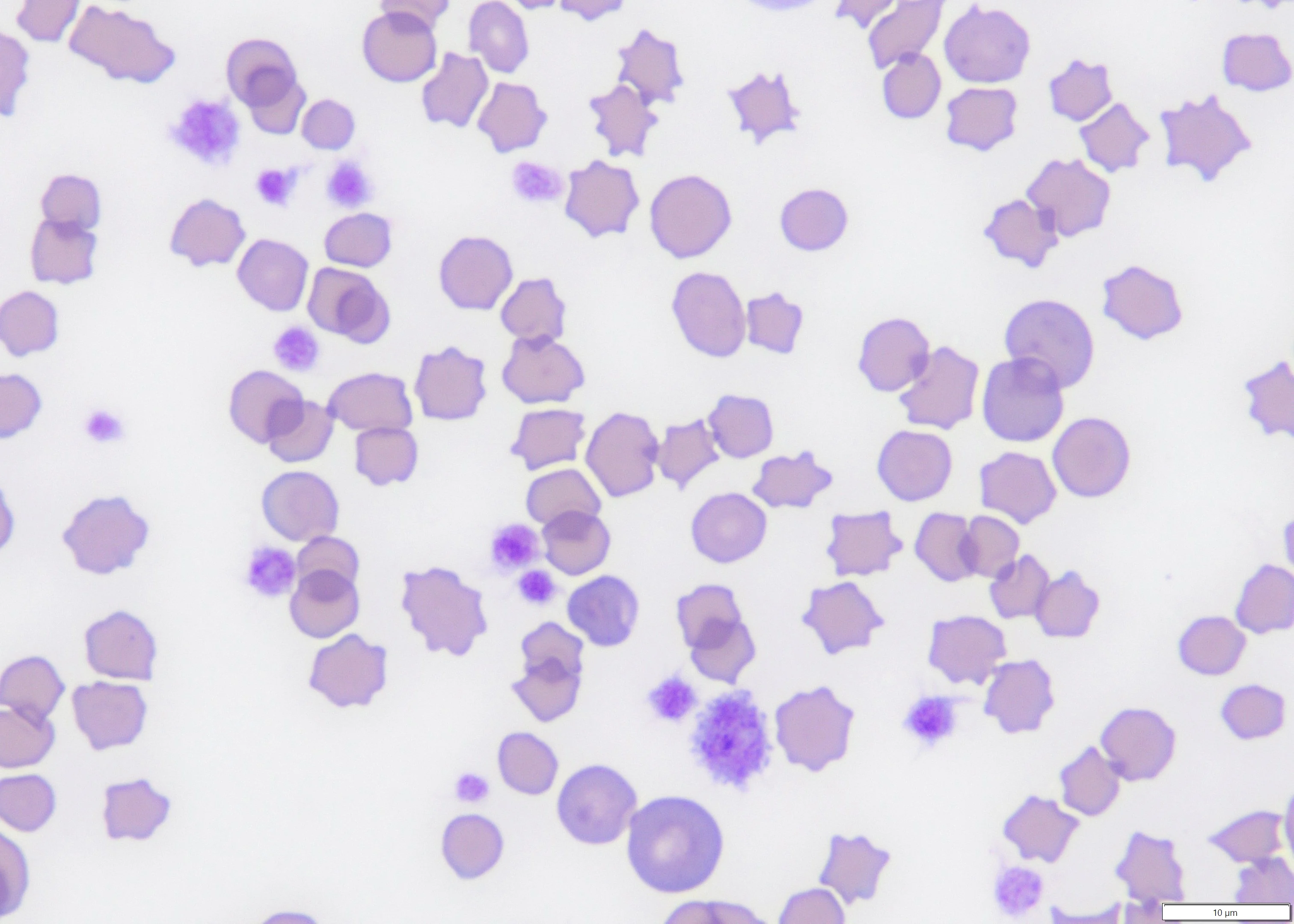

Physiologic and reactive thrombocytosis are not typically associated with clinical signs related to elevated platelet count; however, pseudohyperkalemia can result from release of intracellular potassium from excessive platelets during clotting. Use of heparinized plasma can prevent this artifact. Thrombocytosis can also be an artifact (ie, pseudothrombocytosis) when nonplatelet cell fragments (eg, RBC fragments, leukocyte fragments, microorganisms, lipid droplets) are erroneously included in the platelet count.1

Physiologic Thrombocytosis

Physiologic thrombocytosis results from mobilization of platelets from splenic and, possibly, pulmonary pools (see Causes of Physiologic & Reactive Thrombocytosis).2 Up to one-third of platelets can be sequestered in the spleen, and transient, variable thrombocytosis can occur secondary to epinephrine-induced splenic contraction in response to a stressor (eg, exercise, parturition, veterinary clinic visit).3 This thrombocytosis may be accompanied by erythrocytosis, as splenic erythrocytes are also released into the vascular space. Transient thrombocytosis with platelet counts possibly >1,000 × 103/µL is commonly noted 1 to 2 weeks following splenectomy and can last for several months in dogs.4,5

Causes of Physiologic & Reactive Thrombocytosis

Bone fracture

Drug therapy (eg, glucocorticoids, epinephrine, vincristine, erythropoietin)

Endocrine disease (ie, diabetes mellitus, canine hyperadrenocorticism, feline hyperthyroidism)

Exercise

Hemorrhage (acute)

Hepatobiliary disease

Immune-mediated disease

Infection (acute or chronic)

Inflammatory disease (acute or chronic; especially GI and hepatobiliary disease in cats)

Iron deficiency

Neoplasia (especially carcinoma and lymphoma)

Rebound from thrombocytopenia

Splenectomy

Surgery

Trauma

Reactive Thrombocytosis

Reactive thrombocytosis is associated with a variety of conditions; can be mild (500-800 × 103/µL), moderate (801-1,000 × 103/µL), or severe (>1,000 × 103/µL); and can be transient or persistent. This condition is caused by hormonal/cytokine stimulation of thrombopoiesis. The hormone thrombopoietin, which is produced in the liver and kidneys, promotes stem cell differentiation along the megakaryocytic lineage and acts synergistically with other hematopoietic factors, including stem cell factor, interleukin (IL) 3, and erythropoietin.1 Platelet formation is also stimulated by thrombopoietic cytokines, including granulocyte–monocyte colony-stimulating factor and inflammatory cytokines (eg, IL-1 alpha, IL-6, IL-11, IL-12).6

Studies have identified inflammation and neoplasia as the most common triggers in dogs and cats with nonphysiologic thrombocytosis, with marked thrombocytosis more likely to occur with neoplasia.7-10 Carcinoma, closely followed by lymphoma, was most often associated with thrombocytosis in dogs, and one study documented significantly higher thrombopoietin concentrations in dogs with carcinoma.11 Platelet counts were higher in dogs with neoplasia if the dogs were also anemic (hematocrit, <35%), possibly related to increases in thrombopoietin.12 GI tract disease (including GI lymphoma) and hepatobiliary disease were most often observed in cats with thrombocytosis. Thrombocytosis was also seen in dogs and cats with certain endocrine diseases (ie, diabetes mellitus, canine hyperadrenocorticism, feline hyperthyroidism) or immune-mediated disease.

Thrombocytosis can also occur as a rebound reaction following platelet loss due to blood loss, following surgery or accidental tissue damage, and during recovery from the suppressive effects of chemotherapy.1 Thrombocytosis via an unknown mechanism that appears independent of cytokine levels is common in patients with iron deficiency anemia.1 Drug-induced thrombocytosis has been associated with glucocorticoids, vincristine, and erythropoietin in animals and iron sulfate, ciprofloxacin, piperacillin/tazobactam, retinoic acid, clozapine, and low-molecular–weight heparin in humans.1

Primary Thrombocytosis (ie, Essential Thrombocythemia)

Prolonged thrombocytosis can be seen with essential thrombocythemia, a chronic myeloproliferative disease (clonal disorder of megakaryocytes) that is rare in animals and characterized by marked thrombocytosis, normal WBC and RBC counts, and bone marrow megakaryocytic hyperplasia.13-15 Platelets can vary widely in size, with giant forms in peripheral circulation. Thrombocytosis can also occur with other myeloproliferative diseases, including polycythemia vera, myelofibrosis, chronic myeloid leukemia, and myelodysplastic syndrome. Dysplastic erythrocytes and/or granulocytes are suggestive of one of these diseases. Criteria for diagnosing human essential thrombocythemia based on excluding other causes of thrombocytosis have been developed, and a modified version was used to diagnose essential thrombocythemia in a dog and a cat (see Criteria for Diagnosis of Essential Thrombocythemia in Dogs & Cats).13,14

Criteria for Diagnosis of Essential Thrombocythemia in Dogs & Catsa

Persistent platelet count >600 × 103/µL

No known cause of reactive thrombocytosis

Hemoglobin <13 g/dL (to rule out polycythemia vera)

Stainable iron in a bone marrow aspirate (to rule out polycythemia vera)

Absence of collagen fibrosis on bone marrow examination (to rule out myelofibrosis)

a Modified from the Polycythemia Vera Study Group of the National Cancer Institute for diagnosis of human essential thrombocythemia

Consequences of Thrombocytosis

Reactive thrombocytosis typically resolves over time, after resolution of the inciting cause. Thromboembolic complications are uncommon—even in patients with severe thrombocytosis—but can occur if severe thrombocytosis persists. In humans, prolonged thrombocytosis due to essential thrombocythemia can result in bleeding or microvascular thrombosis with possible CNS ischemia, myocardial infarction, or skin ulceration/necrosis.1 There are few documented cases of severe thrombocytosis causing thrombohemorrhagic events in animals. One retrospective study identified thromboembolism (primarily pulmonary) in several dogs; however, these dogs had other known risk factors (eg, exogenous glucocorticoid therapy, hyperadrenocorticism, hypertension).7 Aortic thromboembolism was documented in a cat with pulmonary carcinoma and paraneoplastic thrombocytosis.16 Low-dose aspirin or clopidogrel should be considered in patients with clinical signs (eg, hemoptysis, increased respiratory effort, pelvic limb pain and weakness) suspicious for thromboembolic complications.

Conclusion

Pseudothrombocytosis should be ruled out by assessing platelet numbers in a stained blood smear. Reactive thrombocytosis is more common than primary thrombocytosis in humans and animals. Thromboembolism may be a concern but is rare in animals with reactive thrombocytosis. The underlying condition is typically the cause of serious disease and should be the focus of primary treatment.