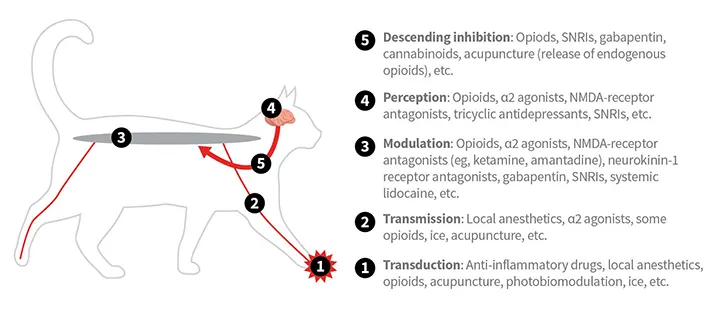

For effective control of surgical pain, analgesic drugs should be included in the preanesthesia, maintenance (intra- anesthesia), and recovery (postanesthesia) phases of the anesthetic protocol.1-6 Drugs should be chosen based on their mechanism of action in the pain pathway (Figure 1). Drugs approved for the species being treated should be used whenever possible.

Sites of action of select analgesic drugs and techniques in the mammalian pain pathway

Following are the author’s top 5 analgesic drugs/drug classes used in surgical pain protocols in cats (also see Tables).

1. Gabapentin (preanesthesia, potentially postanesthesia)

Fearful/anxious or fractious cats may benefit from receiving gabapentin, an anxiolytic, prior to travel to the clinic.7 Although the efficacy of gabapentin for acute pain relief is undetermined, decreased anxiety alleviates the intensity of pain in humans,8 and this same anxiety–pain relationship is thought to apply to cats because of the commonality of human and animal pain/fear/anxiety pathways. There are several case reports and one study involving use of gabapentin for control of acute pain in cats.9 Gabapentin may be more effective in patients with chronic, particularly neuropathic, pain.10 Patients undergoing anesthesia for treatment of chronic pain conditions and/or patients with pre-existing chronic pain undergoing anesthesia for other conditions could potentially benefit from gabapentin.10

*This discussion primarily applies to healthy cats but, depending on the disease and the drug dose, all or most of these drugs are appropriate for diseased cats. More information describing clinical use of these drugs in patients with comorbidities is available (see Suggested Reading). This list of drugs is a generalization, and sources of variability (eg, procedure, patient, surgeon, disease) should be considered for individual patients.

Although not all of the drug classes discussed need to be used in all patients, the author commonly uses all 5 together, especially for treatment of moderate to severe pain. No drug–drug interactions using these combinations have been experienced by the author, but, of note, interactions can occur anytime drugs are coadministered. In addition, all drugs can have adverse effects. These topics are outside the scope of this article. Major concerns are included in this discussion, and references have been included for further reading. However, this is not an exhaustive review of the literature on this topic, and many other references are available.

Table 1: Pre-, Intra-, & Postoperative Analgesic Drug Dosages for Acute Pain Relief in Cats

2. Opioid/α2 Agonist Combination (preanesthesia, commonly postanesthesia)

Using opioids in combination with α2 agonists can provide analgesia of greater intensity and/or longer duration, generally allowing a lower dose of each drug class.11 Opioids commonly used in cats include morphine, methadone, hydromorphone, fentanyl, and buprenorphine. Butorphanol is an effective sedative in most cats, but the duration of analgesia is extremely short (≈90 minutes)12 and, as with most opioids, is variable among individual patients.5,12-14 A feline-specific, FDA-approved formulation of buprenorphine provides 24 hours of analgesia with a single SC injection.15 Although opioids are not needed in every procedure, it is the opinion of the author and pain experts that opioids should be used for surgical pain, especially if pain is expected to be moderate to severe.1-6 If opioids are not available, multimodal analgesic options should be emphasized and the α2 agonist dose can be increased (using the high end of the dose range). Opioid-mediated hyperthermia can occur in cats and is most often related to hydromorphone.4,5

α2 agonists (eg, medetomidine, dexmedetomidine) are classified as sedative-analgesic drugs, and dexmedetomidine is FDA-approved for use in cats.16 The reversible effects of α2 agonists can provide benefits of both safety and convenience. Because α2 agonists are effectively administered IM, cats can be sedated without the undue stress of restraint that is often necessary for IV injection. Although α2 agonists should not be administered to most cats with clinical cardiac disease, α2-mediated bradycardia may be beneficial in some cats with left ventricular outflow obstruction.17 Other comorbidities may need to be considered but are not necessarily contraindications. More information is available for the clinical use of α2 agonists in cats with comorbidities (see Suggested Reading). If α2 agonists are not available, the high end of the opioid dose should be considered and other sedatives added, if needed.

3. Local Anesthetic Blocks (intra-anesthesia, effects last into postanesthesia)

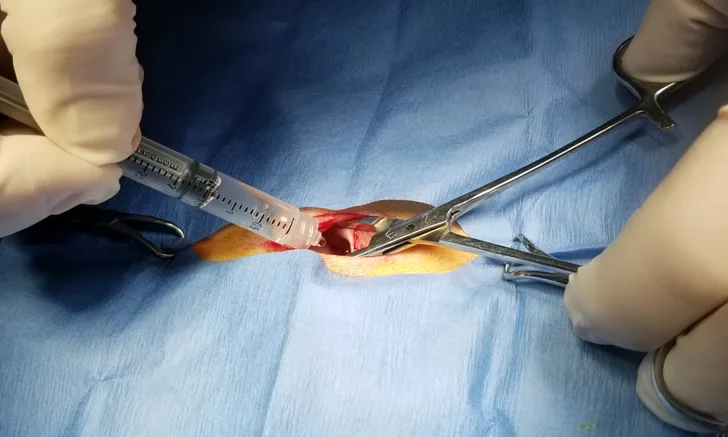

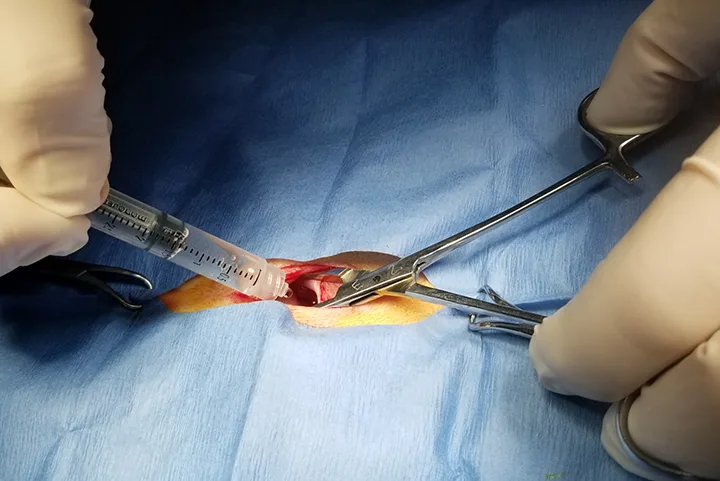

Local/regional anesthesia should be considered as part of a multimodal protocol for pain relief after every surgery and traumatic injury.1-5,18,19 Local anesthetic drugs block pain transmission to the CNS, making them highly effective analgesics.18 Most of these drugs are inexpensive and most blocks are relatively easy to administer.1-5,18,19 In most patients, local anesthetic blockade provides profound pain relief (block-, drug-, and procedure-specific) both during the procedure and into recovery, beyond the drug’s expected duration of action.20-22 This is an important mechanism because it can be complicated to treat pain during recovery in some patients due to limited options and potential drug contraindications with specific diseases (eg, NSAIDs in most patients with renal disease). Local/regional blockade also decreases surgery-related chronic pain development in humans,23 and due to the commonality of the mammalian pain pathway, this effect is predicted to occur in cats. Lidocaine, bupivacaine, and ropivacaine are commonly used local anesthetics in cats. Liposome-encapsulated bupivacaine provides analgesia for 72 hours, is FDA-approved for use in cats for peripheral nerve blocks,24 and is commonly used for other blocks.18,19 Local and regional techniques for cats include oral blocks,1-5,18-20,25 coccygeal epidurals,1-5,18,19,26,27 lumbosacral epidurals,1-5,18,19,28 testicular blocks,1-5,18,19,29,30 and uterine/ovarian blocks or peritoneal lavage (Figure 2).1-5,18,19,21,22,31-33

Local anesthetic drugs are instilled into the abdomen through the open incision for postanesthetic relief of pain following ovariohysterectomy and other abdominal procedures.

4. Ketamine Infusion (intra-anesthesia, potentially pre- and/or postanesthesia)

Ketamine is an N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)-receptor antagonist that has a well-documented role in both acute34 and chronic35 pain control in humans through prevention and treatment of central sensitization, which is an amplification of the pain stimulus primarily due to activation of the normally inactive NMDA receptors. Ketamine is administered at a subanesthetic dose to directly antagonize NMDA receptors. This is a unique mechanism of action as compared with other analgesic drugs. Research in veterinary patients is limited but promising.9 Ketamine infusions are commonly administered to cats, easy to make/administer, and inexpensive.1-5,9,10 Adverse effects with the subanesthetic infusion dose are uncommon, even in patients that have comorbidities.1-5,9,10

Table 2: Local Anesthetic† Drug Dosages, Time to Onset, & Duration of Action for Acute Pain Relief in Cats

†All drugs in this chart can be used for tissue infiltration and perineural injection. Lidocaine, bupivacaine, ropivacaine and mepivacaine can also be injected epidurally.

5. NSAIDs (postanesthesia, potentially preanesthesia)

The main source of surgical pain is inflammation; thus, NSAIDs are a crucial component of effective analgesia. NSAID administration can be initiated pre- instead of postanesthesia, depending on the likelihood the patient will develop hypotension or hypovolemia during surgery.1-6,36 If used postanesthesia, an injectable NSAID is recommended by the author to enable pain relief prior to return to swallowing, at which point administration of oral medication is deemed safe. NSAIDs should be dispensed for administration at home, with the treatment duration dependent on the expected duration of pain. Both meloxicam (single dose) and robenacoxib (3 daily doses) are approved for treatment of acute pain in cats in the United States37,38; however, the clinically recommended meloxicam dose (0.1 mg/kg) is lower than the labeled dose (0.3 mg/kg).36 In many countries outside the United States, both drugs are approved as long as pain is present.39,40 For more effective pain control, opioids can be used when pain cannot be controlled by NSAIDs alone and in patients in which NSAIDs are not appropriate.41 Buprenorphine can be administered oral transmucosally, although the uptake is not as predictable as once thought, and is likely to produce a varied response5,12-14; this dose may need to be higher (0.01-0.05 mg/kg) than the injectable dose.14 Federal and state laws should be followed when dispensing opioids.

Conclusion

For any painful procedure, regardless of the perceived efficacy of the analgesic protocol, assessment of pain—and pain relief following analgesic administration—is a critical component of appropriate patient care. Validated pain scoring systems for acute pain assessment in cats are available.40-46