Top 5 Inappropriate Antibiotic Uses in the Emergency Setting

Beth Davidow, DVM, DACVECC, Washington State University

Prompt administration of the appropriate spectrum and dose of antibiotics decreases mortality from sepsis1,2; however, inappropriate use of antibiotics can put patients at risk for adverse effects and promote development of resistance.3,4

Making decisions in an emergency situation can be difficult when disease may be acute and severe, and pet owners may ask for antibiotics even if administration is not indicated. The International Society for Companion Animal Infectious Diseases (ISCAID) has developed treatment guidelines to help improve antibiotic stewardship in patients with urinary, respiratory, and skin conditions.5-7 These guidelines can be useful in the development of protocols that promote consistent care and avoid antibiotic prescription errors.

Following are the author’s top 5 inappropriate uses of antibiotics in the emergency setting with alternative treatment suggestions.

1. Amoxicillin/Clavulanic Acid to Treat Upper Respiratory Infection & Community-Acquired Pneumonia

Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid is a well-tolerated bactericidal antibiotic commonly used in emergencies. This drug is an aminopenicillin combined with a beta-lactamase inhibitor that provides broad-spectrum coverage with good activity against gram-positive aerobes and anaerobes as well as some gram-negative bacteria. Despite its usefulness, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid has limited in vivo activity against common upper respiratory pathogens in cats and dogs.

Most cats with upper respiratory infections (URIs) have a viral, not bacterial, etiology.5 Although Chlamydia spp and Mycoplasma spp can cause URIs in cats, these bacteria are not susceptible to amoxicillin/clavulanic acid. Bordetella spp are sensitive to amoxicillin/clavulanic acid in vitro, but the antibiotic is not effective in clinical disease due to inadequate bronchial penetration.5 Bordetella spp can cause coughing and other upper respiratory signs in cats. ISCAID recommends only considering antibiotics if fever, lethargy, mucopurulent discharge, and anorexia are all present.5 Doxycycline is recommended if antibiotics are deemed necessary, as Chlamydia spp, Mycoplasma spp, and Bordetella spp are all susceptible to doxycycline.5

Dogs with URIs can also have either viral or bacterial etiologies, and antibiotics may not be needed. In otherwise healthy dogs that are eating well and active but have a cough, treatment with a cough suppressant and isolation from other dogs may be sufficient. In a single retrospective cohort study, trimethoprim/sulfonamide appeared to slightly decrease the duration of cough from 10 to 7 days8; however, there are no prospective controlled trials evaluating recovery rates for dogs with suspected infectious tracheobronchitis with or without antibiotics.8 ISCAID recommends waiting to administer antibiotics unless there is evidence of lethargy, anorexia, and fever along with cough in an otherwise healthy dog. Doxycycline is also the recommended choice for dogs if antibiotics are required.5

In a study of dogs with community-acquired pneumonia, Bordetella bronchiseptica was a commonly isolated bacterium,9 and 24 out of 32 dogs with B bronchiseptica were administered either amoxicillin or amoxicillin/clavulanic acid prior to presentation with no improvement in clinical signs,9 despite in vitro sensitivity. Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid may not achieve adequate levels in the airways; thus, doxycycline is preferred, even in cases in which URI progresses to pneumonia.5,9

2. Antibiotics for Treatment of Urinary Tract Signs Without Confirming Infection

Most young cats with urinary tract signs have feline idiopathic cystitis, which is a noninfectious condition,6,10,11 and <10% of cats with urinary tract obstruction have a concurrent bacterial infection.12 A study suggested that only 53% of dogs presented with lower urinary tract signs had bacterial cystitis,13 and 36% of dogs without bacterial cystitis were inappropriately prescribed antibiotics.

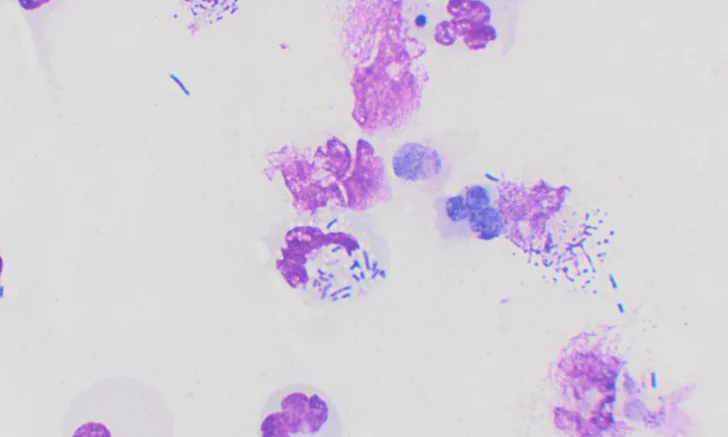

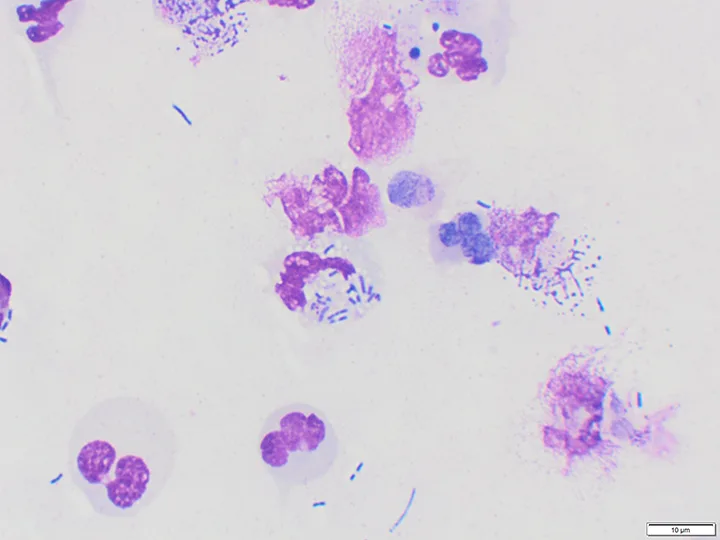

Two studies have shown excellent sensitivity and specificity in diagnosing bacterial cystitis via identification of intracellular bacteria using modified Wright-Giemsa or Gram stain of air-dried urinary sediment. (Figure 1).14,15 Culture and susceptibility testing is recommended prior to antibiotic administration, especially in patients that have received antibiotics in the last 60 days or have acquired infection while in the hospital.6,16 Urine culture should be submitted promptly after collection. If this is not possible, the sample should be refrigerated prior to submission.6

If urine cannot be obtained in a young cat with signs of cystitis, supportive treatment (eg, pain medication, environmental management) for feline idiopathic cystitis is the preferred approach.6 Owners should be informed that clinical signs may take 3 to 7 days to resolve. Urinalysis is imperative in dogs because the incidence of infection is higher but not always the cause of clinical signs.13

Urine sediment dried and stained with Wright-Giemsa stain demonstrating degenerate neutrophils and intracellular bacteria (50× oil). Image courtesy of Michelle Decourcey, DVM, Washington State University

3. Antibiotics for Treatment of Acute Diarrhea in Dogs

The use of antibiotics for treatment of acute diarrhea in dogs has been questioned.17,18 In one study, dogs with hemorrhagic gastroenteritis without sepsis were administered either a placebo or amoxicillin/clavulanic acid.17 No difference was observed in the severity of clinical signs, mortality, or hospitalization times between the groups. In a recent study, stable dogs with acute diarrhea were randomized to receive metronidazole, placebo, or a probiotic. Owners kept a log with fecal scores. No statistical difference among the groups was observed in the time to improved stool.18 It is therefore reasonable to avoid antibiotics in dogs with diarrhea that are otherwise stable.

4. Enrofloxacin Twice (vs Once) Daily

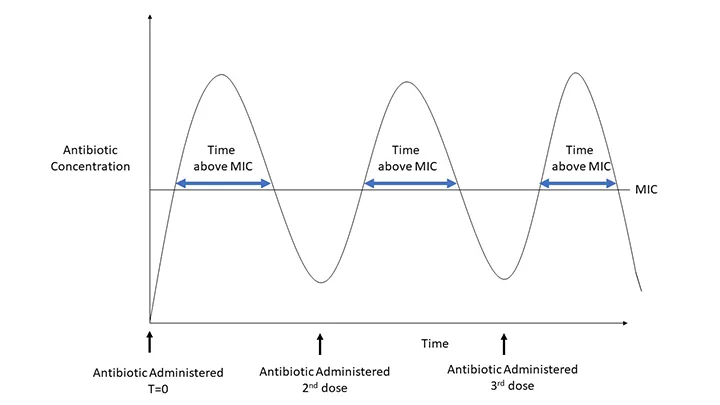

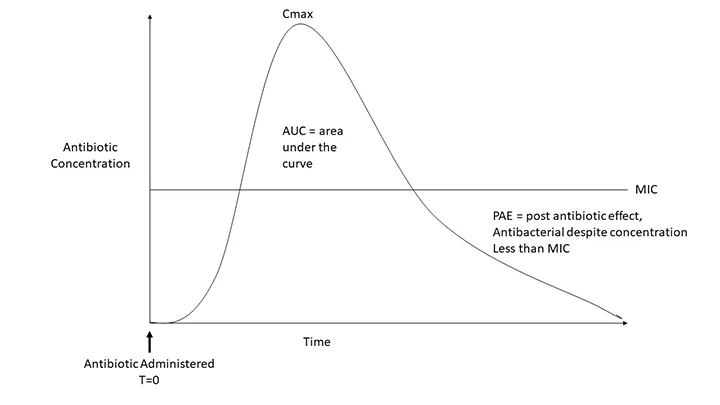

Antibiotics can be categorized as either time or concentration dependent (Figures 2 and 3). Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) is the lowest concentration of antibiotic needed to inhibit bacterial growth. Cm,x is the maximum plasma concentration of the drug attained during the dosing interval. Postantibiotic effect (PAE) is an antibacterial effect that persists despite blood and tissue levels below MIC. The efficacy of time-dependent antibiotics, including penicillins and cephalosporins, is based on the total time over MIC; these antibiotics exhibit limited PAE. The efficacy of concentration-dependent antibiotics, including fluoroquinolones and aminoglycosides, is based on Cm,x or area under the curve and often has significant PAE.19

With time-dependent antibiotics, increased frequency improves efficacy; therefore, amoxicillin should be administered every 8 to 12 hours.6 With concentration-dependent antibiotics, increased dose improves efficacy; thus, fluoroquinolones are more effective when given at a higher dose every 24 hours.19

The efficacy of time-dependent antibiotics is based on the total time the antibiotic concentration is above MIC, thus increased frequency of administration improves effectiveness.

The efficacy of concentration-dependent antibiotics is based on Cmax and area under the curve rather than on time above MIC. Many of these antibiotics also have PAEs.

5. Routine Use of Prolonged Antibiotic Courses

Many disease studies in humans demonstrate that short antibiotic treatment courses are as effective as prolonged courses for most conditions.20,21 This is also true for septic peritonitis, pyelonephritis, and pneumonia, in which courses of 4 to 10 days are routinely recommended.22,23 Antibiotics given to dogs with pneumonia for <14 days were as effective as longer courses in both resolution of signs and prevention of recurrence.24

Conclusion

Antibiotics can be lifesaving but should only be used when required. Coverage spectrum, dosage, and length of treatment should be carefully considered.